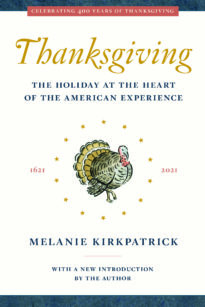

Americans will gather in 2021 to mark the four hundredth anniversary of what has come to be known as the First Thanksgiving. As we do so, it is sadly necessary to come to the defense of the holiday.

Thanksgiving is our oldest tradition, celebrated by almost every native-born citizen as well as by newcomers to this country, for whom it is a rite of passage into the American family. No matter where in the world we find ourselves on the fourth Thursday of November, Americans come together to give thanks—fulfilling the prediction of Sarah Josepha Hale, the nineteenth-century magazine editor by whose singular efforts Thanksgiving was transformed from a series of local celebrations on various dates into a shared national one.

The felicitous custom of the holiday demands that no one be excluded. The widowed aunt, the grouchy grandpa, the coworker with nowhere else to go—all receive invitations to dinner on Thanksgiving Day. Americans on the margins of society are included in the celebration thanks to the generosity of individuals, religious organizations, and philanthropies that make sure the less fortunate among us have an opportunity to mark the day. Everyone has a place at the nation’s Thanksgiving table, regardless of circumstances or creed. President George Washington set the example in his Thanksgiving proclamations when he urged that the celebration be open to people of all faiths.

If this depiction of Thanksgiving reflects what you put into practice every year in late November, increasingly loud voices are telling you to think again. In the few short years since this book was first published, Thanksgiving has come under unprecedented assault from progressives who want to expunge it from American life. In our woke era, it has become fashionable in some quarters to attack Thanksgiving on the grounds of cultural exploitation. Left unmentioned are gratitude and God.

Given recent attacks on Washington, Lincoln, and other heroes of American history, it was only a matter of time before cancel culture came for Thanksgiving. That moment arrived on Thanksgiving Day 2020, when vandals went on a crime spree in several cities under the guise of advancing Native American rights. They smashed storefronts and defaced statues with slogans such as “no thanks,” “no more genocide,” “decolonize,” and “land back.”

Another slogan, “Pequot Massacre,” propagated a slur found, incredibly, in some high school history classes: that the chief precedent for our holiday was the early settlers’ practice of giving thanks for victories in skirmishes with natives, or as the cruder version of the story has it, to celebrate the murder of Indians. This is a dishonest take on the origin of Thanksgiving, which grew from multiple and varied roots. The practice of giving thanks for military victories—as Washington, John Quincy Adams, and every wartime president since Lincoln and Jefferson Davis have done in Thanksgiving proclamations—is but one of many sources of the holiday.

The truth about the relationship between Native Americans and Thanksgiving is more complicated than the holiday’s detractors would have us believe.