In the fall of 1800, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth unexpectedly resigned as Chief Justice, marking the fourth transition of Chief Justices in the Court’s first eleven years of existence. By now it was clear that President John Adams’s party, the Federalists, had lost the presidency and control of the Senate, so Adams was under intense pressure to appoint a new Chief Justice quickly, before the Democratic-Republicans took over.

Adams’s first choice was to ask John Jay, the inaugural Chief Justice of the United States from 1789 to 1795, to take the job again after a break spent negotiating a peace treaty with the British and serving as Governor of New York. Jay was a strong choice. He was well respected amongst his contemporaries and would lend some needed heft, politically and intellectually, to a struggling branch of the government. He also knew the job and what it entailed, which is what actually doomed the possibility from the start.

Jay knew the job too well and declined, citing the challenges of riding circuit (where Justices traveled widely to hold court) and his disappointment in the current state of the Court. Jay’s blunt description of the many flaws of the Supreme Court pre-Marshall is incredible to modern readers:

I left the bench perfectly convinced that under a system so defective it would not obtain the energy, weight, and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government; nor acquire the public confidence and respect which, as the last resort of the justice of the nation, it should possess. Hence I am induced to doubt both the propriety and the expediency of my returning to the bench under the present system.

Adams was now in a tight spot. He needed to appoint a new Chief Justice in the remaining six weeks of his presidency, while the Federalists still controlled the Senate. John Marshall was serving as the Secretary of State and appears to have been in the right place at the right time. Marshall describes Adams’s decision:

When I waited on the President with Mr. Jay’s letter declining the appointment he said thoughtfully, “Who shall I nominate now?” I replied that I could not tell. . . . After a moment’s hesitation he said, “I believe I must nominate you.” I had never before heard myself named for the office and had not even thought of it. I was pleased as well as surprised and bowed in silence. Next day I was nominated.

The appointment of Marshall is thus one of the great “what ifs” in American history. What if Jay had accepted? Could or would he have shepherded the Court into existence as Marshall did? Even better, what if Hamilton had agreed to become Chief Justice rather than Ellsworth in 1796? He probably would not have resigned in 1800 and Marshall might have left government service to return to his law practice and land speculation in Virginia.

***

As it was, Marshall served longer than any other Chief Justice, more than thirty-four years. He used that time to create the modern Supreme Court. When Marshall joined the Court in 1801, it was not yet clear that the Supreme Court would be the final word in the interpretation of the law or the Constitution. It was not yet clear that the Supreme Court would have the power to invalidate federal or state law. It was not even clear that the Supreme Court’s rulings would govern matters of state law. Under Marshall the Supreme Court’s power extended into each of these areas in a series of unanimous or nearly unanimous decisions that he himself wrote.

When Marshall joined the Court in 1801, it was not yet clear that the Supreme Court would be the final word in the interpretation of the law or the Constitution.

Marshall also changed the decision writing process itself. Before Marshall, each Justice tended to write his own opinion in deciding a case. Marshall instituted the tradition of a single majority opinion stating the controlling law, as well as the occasional dissent.

Marshall wrote almost every seminal Supreme Court decision during this formative era for the Court and the nation. There are too many foundational opinions to cover here, but allow me a brief review of two of Marshall’s greatest hits. Marshall wrote Marbury v. Madison, which was the first case to squarely hold an act of Congress unconstitutional. This may be the single most famous Supreme Court opinion and is credited with settling once and for all the Supreme Court’s power of constitutional review.

Marbury is also a great introduction to Marshall’s over-the-top and plain-spoken writing style. Marshall liked to start from first principles and reason to conclusions, often with generous helpings of hyperbole along the way. Marshall wrote with few references to precedent or law. Here is a typical portion of Marbury:

If an act of the legislature, repugnant to the constitution, is void, does it, notwithstanding its invalidity, bind the courts, and oblige them to give it effect? Or, in other words, though it be not law, does it constitute a rule as operative as if it was a law? This would be to overthrow in fact what was established in theory; and would seem, at first view, an absurdity too gross to be insisted on. It shall, however, receive a more attentive consideration. It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each.

In a case where the sitting President of the United States (Thomas Jefferson) and the Secretary of State and one of the principle architects of the Constitution (James Madison) disagreed with him on the role of the Court, Marshall calls their argument “an absurdity too gross to be insisted on” and then answers his own question “emphatically,” all with no citations. Humorously, this passage is pretty typical for a high-salience Marshall opinion. The higher the stakes, the more heated his rhetorical style and the more unsubtle his reasoning.

From Marshall through Stephen Field and on to Sandra Day O’Connor there is a rich history of Justices who cut their teeth in the rough and tumble of the relatively unsettled American frontier.

McCulloch v. Maryland is another Marshall classic. Here the Court held that it was constitutional for Congress to create the Second Bank of the United States under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution, even though the power to do so was not explicitly expressed in the Constitution.

Marshall approached the question with his usual logic, leavened with rhetorical flourish: “If any one proposition could command the universal assent of mankind, we might expect it would be this—that the Government of the Union, though limited in its powers, is supreme within its sphere of action.” And what of the opposing argument, that Congress was strictly limited to enumerated powers, and that the necessary and proper clause could not support the creation of a federal bank? Marshall hotly retorted that “the inevitable consequence of giving this very restricted sense to the word ‘necessary,’ would be to annihilate the very powers it professes to create; and as so gross an absurdity cannot be imputed to the framers of the constitution, this interpretation must be rejected.”

So, just to summarize, Marshall’s version of constitutional interpretation is the single proposition most likely to “command the universal assent of mankind,” and the opposing argument (also known as strict constitutional construction, an interpretive strain that still holds considerable sway today) was “so gross an absurdity” that it was rejected out of hand. Marshall followed these bon mots by explaining that the power to establish a federal bank was implied by various other enumerated powers and that “[w]e must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding.” Justice Frankfurter considered this Marshall quote the single greatest statement of the Court’s purpose in constitutional interpretation.

Please permit me a short aside here. A dear friend and expert constitutional law scholar thinks I have been “a little too hard” on Marshall’s opinion in McCulloch here. This is exactly the opposite of my intent. Marshall’s opinion is praiseworthy precisely because of its rhetorical flourishes and appeals to logic rather than to a more technical legal approach. One of the reasons I love Marshall’s writing and respect him as a jurist is because he knew when to bring the wood. Marshall set the model for the greatest Supreme Court opinions, which start with obvious, well-worn truths and finish with the legalities—not the other way around. Reread Brown v. Board of Ed., Gideon v. Wainwright, Loving v. Virginia, or the dissents in Dred Scott, Plessy v. Ferguson, or Olmstead v. U.S. with Marshall in mind and you will hear him echoed in style and content.

***

Marshall’s background is almost the polar opposite of the current model. Marshall grew up on what was then the frontier of Virginia, in Fauquier County, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. His father, Thomas Marshall, worked as a surveyor and land agent for Lord Fairfax, exploring the western portions of Virginia that eventually became Kentucky and West Virginia. As a surveyor Thomas Marshall was able to purchase particularly promising land, and Marshall’s family moved three times in his childhood, always west onto newly surveyed land. For the first fifteen years of his life, Marshall’s family lived in two different four-room cabins built by his father. Marshall was the oldest of fifteen children, and while his father eventually accumulated land and means, Marshall remembered a modest childhood: the family made most of their own clothes and grew their own food. Marshall is thus one of the many “frontierspeople” to make it to the Supreme Court. From Marshall through Stephen Field and on to Sandra Day O’Connor there is a rich history of Justices who cut their teeth in the rough and tumble of the relatively unsettled American frontier.

Like other Justices before and after him, Marshall had little formal education of any kind. Partially self-taught, home schooled, and tutored by clergy, Marshall learned what he needed to know largely through his parents and on his own. Marshall’s only stint of organized, formal education was “law school” at William and Mary with George Wythe. As historian Herbert Alan Johnson explains:

Judged by the standards of the present day, or even those of eighteenth-century colonial America, John Marshall was given a paltry foundation in the law. Six weeks of attendance at George Wythe’s law lectures at William and Mary were supplemented by some common-placing from Bacon’s Abridgement. . . . Marshall for the most part was a lawyer who learned his law while he practiced it.

Self-education has virtually disappeared in modern America, but it is worth noting that Marshall came from a modest educational background even amongst his contemporaries. Marshall replaced Oliver Ellsworth, who had attended Yale and Princeton, and served with William Paterson, a Princeton graduate, and William Cushing, a Harvard graduate. Elite educational backgrounds on the Court are not new, we just used to put less stock in them.

Elite educational backgrounds on the Court are not new, we just used to put less stock in them.

Marshall spent a large chunk of his early adulthood fighting in the Revolutionary War. In the summer of 1775, nineteen-year-old John Marshall was appointed a First Lieutenant in the Fauquier Rifles, a unit of the Culpeper Minutemen. For the next five years Marshall served bravely, fighting in the siege of Norfolk, the Battle of the Brandywine, the Battle of Monmouth, and suffering through the brutal winter of 1777–78 in Valley Forge. No current Justices have spent any time outside of ROTC or the reserves in the military, let alone anything resembling Marshall’s formative combat experience.

Justice Marshall then cut his teeth as a lawyer in solo practice, handling trials and appeals alike. Marshall sometimes handled as many as 300 cases a year. He handled criminal and contracts cases. Marshall built one of the most successful law practices in Virginia from virtually nothing. During his first years of practice he had few clients and less money. These early years were rocky enough that some biographers have argued that Marshall was a great statesman, but a poor lawyer. Marshall’s eventual success belies this claim, however. By the time Marshall entered full-time government service he was among the very best-known lawyers in Virginia, America’s most populous state in the late-eighteenth century. The legal work experiences of current Supreme Court Justices reflect that they were the best of the best coming out of law school and clerkships. Marshall’s achievements reflect the success that comes from rising up within the practice by serving regular people on all sorts of legal issues.

Justice Marshall was more than just a lawyer though. He was an entrepreneur, a land speculator, and a hustler. In these activities he followed in the footsteps of his father, who himself built a fortune exploring Virginia and buying up prime acreage for later, profitable resale. Before Marshall joined the Court, he and other family members purchased more than a hundred thousand acres of prime land in Virginia’s Northern Neck from Lord Fairfax’s heir for a bargain price. But Marshall was actually buying a lawsuit that pitted his property interests against the state of Virginia, which hoped to escheat the land because Lord Fairfax was a foreign national on the losing side of the Revolutionary War. Marshall bet that between the Treaty of Paris (which arguably protected British holdings in America), his skill as a litigator, and his political connections, the land would eventually be his.

The lawsuits over this land lasted for years and eventually ended up in the Supreme Court as the famous 1816 case of Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee, from which Marshall recused himself. That case finally settled title on the land in Marshall’s favor, and he died a wealthy man. But before this victory Marshall faced financial difficulties, which led him to decline appointments as the Attorney General of the United States and as the first U.S. Attorney for the District of Virginia, two posts that were significantly less lucrative than his booming private practice. Some of Marshall’s wealth came from being a slave-owner. He owned as many as 150 slaves in his life, but he also considered slavery an evil institution that damaged slaves and slave owners alike. Like many slave-owning founders, he argued that the institution should be abolished.

John Marshall’s biography and successes are in some ways a reminder of a different America that was packed with able generalists who were pressed into all sorts of activities by circumstances, from high level diplomacy to front line combat to the solo practice of law and eventually running the Supreme Court.

John Marshall was also politician, and he is generally considered to have been a rather able one. At twenty-seven he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for the area around Fauquier County where he grew up and five years later for the county near Richmond where he then lived as a lawyer. He also served on the Virginia Council of State (an executive supercommittee) from 1782 to 1784 along with James Monroe. Marshall’s greatest electoral victory was to the United States House of Representatives in 1798. Marshall ran as a Federalist against an incumbent Democratic-Republican in a state dominated by powerful Democratic-Republican politicians (notably Thomas Jefferson and James Madison) and won, a remarkable upset at the time.

Last, and possibly most importantly, John Marshall is a classic example of what Professor Anthony Kronman has called “the lawyer-statesman.” After refusing several different Federal appointments under George Washington, Marshall agreed to serve President John Adams as one of three peace envoys to France. The mission was critical, as America and France were teetering on the edge of war and France had been seizing American ships in the West Indies. Marshall’s mission to France is now known as the XYZ affair, because three different French emissaries (labeled X, Y, and Z by Marshall to protect their identities) demanded a significant bribe from the Americans before meeting with the French delegation for peace terms. Marshall and the other two envoys refused, and when Marshall’s description of the affair became public in the United States, he was hailed as a hero. After a term in Congress Adams appointed him as Secretary of State. In this position he helped negotiate peace with France at the Convention of 1800. Our current Justices have limited non-legal or executive experience. Certainly none have held positions as important as Secretary of State, or done work like negotiating peace treaties.

John Marshall’s biography and successes are in some ways a reminder of a different America that was packed with able generalists who were pressed into all sorts of activities by circumstances, from high level diplomacy to front line combat to the solo practice of law and eventually running the Supreme Court.

Read more in The Credentialed Court: Inside the Cloistered, Elite World of American Justice.

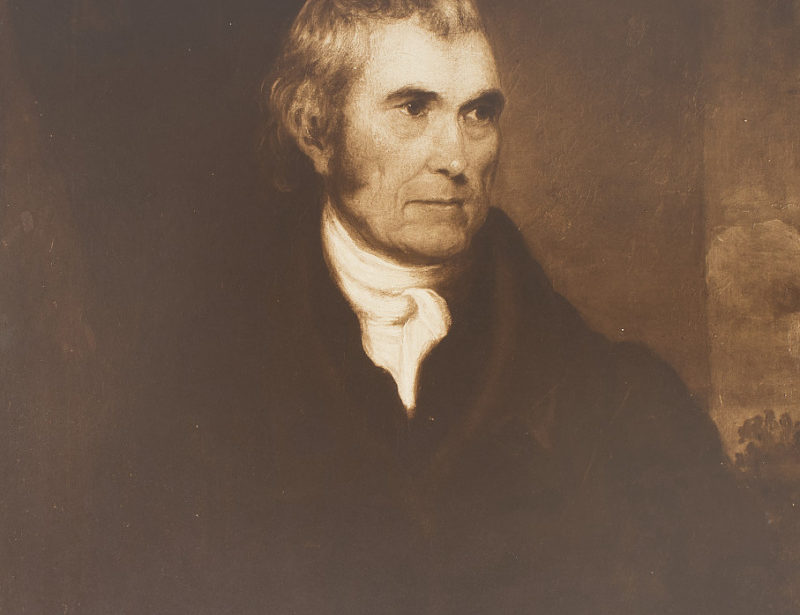

Header image is of the statue of Chief Justice John Marshall in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Source: Mark Skrobola on Flickr.