While it may be hard to fathom given the crybully inhabitants of today’s Ivy League , graduates of America’s elite universities have ascended to the highest halls of power since before the founding of the nation. And the ideas inculcated in them at those institutions have had an indelible impact on the direction of the country since day one.

In Common Sense Nation, Robert Curry tells the remarkable story of a single class at one such college that very nearly spawned the founding and the federal government by itself.

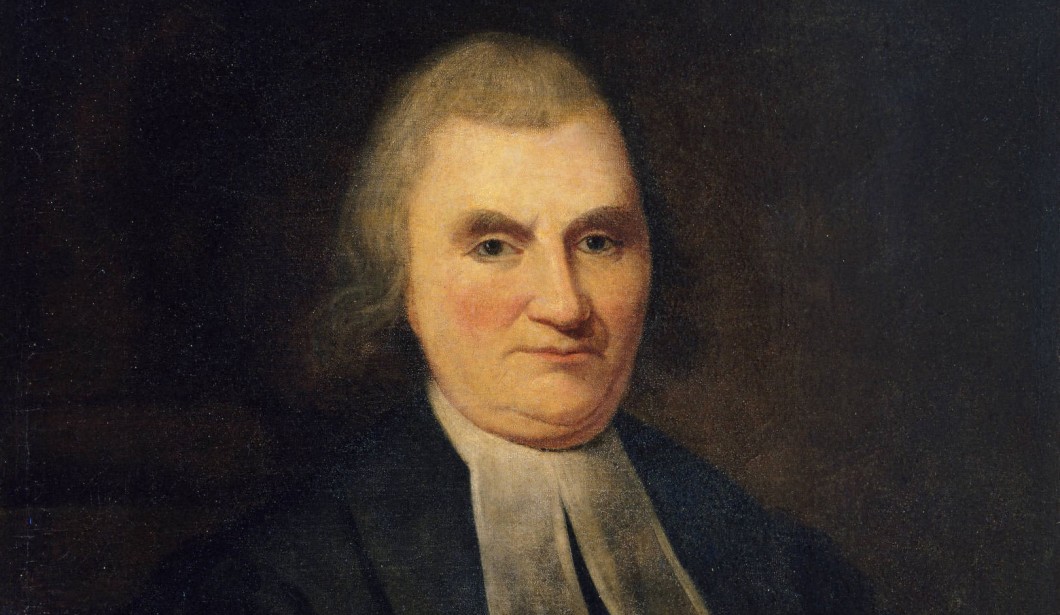

Here’s Curry with more on the class, and its radical teacher—John Witherspoon—that led his school, Princeton, to be known as “the seedbed for revolution”:

[John] Witherspoon is no doubt the most important example of the influence of Scottish educators. In the words of Jeffry Morrison in his biography of Witherspoon:

“No other founder (not even James Wilson) did more to channel the Scottish philosophy into the colonies and thus into American political thought.”

Witherspoon’s students by one count included, among many others, five delegates to the Constitutional Convention, twenty-eight U.S. senators, forty-nine U.S. representatives, twelve governors, three Supreme Court Justices, eight U.S. district judges, three attorneys general, and many members of state constitutional conventions and state ratifying conventions. Is it any wonder that the ideas and arguments of Reid and Smith and their Scottish colleagues are everywhere in the writings of the Founders?

What did Witherspoon teach?

Witherspoon’s course in moral philosophy, which he dictated year after year in largely unchanging form and which his students copied down faithfully, is almost certainly the most influential single college course in America’s history. It borrowed heavily from Hutcheson’s A System of Moral Philosophy, and at its core were the principles of Reid’s common sense realism:

“[There are] certain principles or dictates of commonsense … These are the foundation of all reasoning … They can no more be proved than an axiom in mathematical science.”

Henry May, in his book The Enlightenment in America, points to Witherspoon’s lectures as the source of “the long American career of Scottish Common Sense” which was “to rule American college teaching for almost a century.”

Witherspoon taught his course at an Ivy League institution whose students today — in their zeal, for example, to remove the name from its buildings of a former college and U.S. president — would likely be unrecognizable to Witherspoon and his students. Curry continues:

Princeton was founded by the Presbyterians to provide a college in America for the training of its ministers for America. The American Presbyterian Church was a powerful and united religious organization in the Founders’ generation, and this was an era in which the pulpit mattered to an extent that is very nearly inconceivable to Americans today. As the de facto head of the Presbyterians in America, Witherspoon’s influence was enormous, reaching American communities far removed from college campuses.

Witherspoon’s contributions to the founding extended well past the confines of Princeton:

Beyond his enormous influence as an educator and church leader, Witherspoon was also one of the most important of the Founders. He was an early and influential champion of American independence, and much more than merely a signer of the Declaration of Independence. In fact, he played a central role in the signing.

When the Declaration was completed and ready to be signed, the signers-to-be wavered. For two days they hesitated to affix their signatures. To sign it, after all, was to provide the British with documentary evidence of treason, punishable by death. Witherspoon rose to the occasion, speaking in his famously thick Scottish accent:

“There is a tide in the affairs of men, a nick of time. We perceive it now before us. To hesitate is to content to our own slavery. That noble instrument upon your table, which ensures immortality to its author, should be subscribed this very morning by every pen in this house. He that will not respond to its accents and strain every nerve to carry into effect its provisions is unworthy the name freeman.”

His speech broke the logjam and, as we all know, the delegates then swiftly signed the Declaration.

They truly do not make men like John Witherspoon anymore. And if they did, his teachings would be shrouded with trigger warnings.

For more on Witherspoon, common sense realism and the American founding, be sure to listen to our full podcast interview with Robert Curry below: