Few Americans are aware that Washington is the country’s largest single patron of art. Every year a group of unelected federal bureaucrats and congressmen spends millions of taxpayer dollars on monuments, sculptures, buildings, plays, and exhibitions, largely without public knowledge or involvement. Frank Gehry’s outlandish memorial to President Eisenhower, an installation that blinks quotes from Eleanor Roosevelt in Morse code at a cash-strapped Veterans Administration hospital, a giant $750,000 wood sculpture whose fumes sickened workers in an FBI building in Miami, FL, and funding for research on the visual cultures of tea consumption in Imperial India are just a few of the hundreds of unwanted and wasteful projects supported annually by the General Services Administration, the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, and their enablers on Capitol Hill. In this book, Bruce Cole, the longest serving chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, exposes the programs and policies responsible for this glut of unsupervised bureaucratic pork and offers suggestions for their reform or elimination.

Free shipping on all orders over $40

Art from the Swamp

How Washington Bureaucrats Squander Millions on Awful Art

Publication Details

Hardcover / 152 pages

ISBN: 9781594039966

AVAILABLE: 8/28/2018

- Media: Request a Review Copy

- Academia: Request an Exam Copy

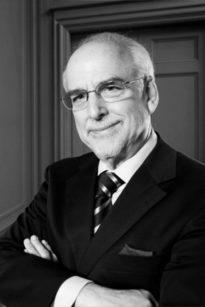

About the Author

Bruce Cole (1938-2018) was a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

IN THE MEDIA

Excerpt

Washington bureaucrats spend millions of dollars each year on artwork and do so without the knowledge or consent of most of the taxpayers who foot the bill. Commissioned by a labyrinthine thicket of unelected commissions, committees, boards, and panels, this art is unwanted, unloved, and astronomically expensive. This book will explore, and often expose, how federal funds are used to produce awful art through an examination of the Eisenhower Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the General Services Administration’s Art in Architecture Program, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

The history of government-sponsored art is a long one. For millennia, public works of art and architecture have been commissioned, and paid for, by rulers. From ancient Egypt to our time, paintings, sculptures, monuments, memorials, and buildings furthered the aims of emperors, kings, popes, and dictators, among others. Pyramids, pagan temples, soaring cathedrals, and untold numbers of paintings, mosaics, and statues tell us as much about the character of those who made them as do words in books and manuscripts.

Our relationship with art and architecture is not merely a one-way street; as Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Sometimes such shaping is evil, as with Albert Speer’s crushing designs for Hitler’s Berlin, and sometimes it is good, as with the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington. This is also true of paintings and sculptures.

This book is about public art commissioned by the government of the United States, a country that has been commissioning works of art for almost as long as it has been independent. In 1783, the year the Revolutionary War ended and five years before the ratification of the Constitution, an equestrian statue of George Washington was commissioned by the Confederation Congress. Although the statue was never created, a precedent was set for federal patronage of art and architecture. The following year, the Virginia General Assembly also commissioned a statue of Washington (which was sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon between 1785 and 1791), an early example of state sponsorship of art.

After Congress held its first session in the District of Columbia in 1800, funds were appropriated for the Capitol, its decoration, and for other federal buildings in the capital city and beyond. For the rest of the nineteenth century and through the early twentieth century, however, art commissions were sporadic and unsystematic.