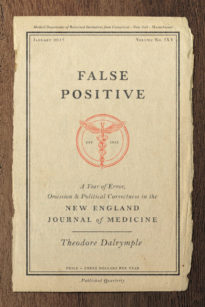

This book is a running commentary, week by week, on the New England Journal of Medicine, one of the most important general medical journals in the world, during the year 2017. It demonstrates that the conclusions of many of the papers in it are not only flawed, but obviously flawed – though for lack of time, many doctors will not examine them closely and will therefore be taken as authoritative. In some cases there is the suspicion of actual corruption. There are errors of reasoning and obvious omissions, apparently undetected by the editors. In addition, in its examination of social questions the Journal is solidly politically correct, and practically no debate on these matters appears in its printed version. Highly debatable points of view go completely undebated. The Journal reads as if there is only one possible point of view, its own, though the American medical profession, to say nothing of its extensive foreign readership, is more than a millions strong and cannot possibly be universally in agreement with the stances it takes. It is thus more megaphone than sounding board – as, in the opinion of the author, it should be. The book is not intended to be destructive, however: praise and admiration are given where the author thinks they are due. However, it should encourage the general reader to be wary of the latest medical doctrines, and to take a constructively critical stand to the latest medical news.

Free shipping on all orders over $40

False Positive

A Year of Error, Omission, and Political Correctness in the New England Journal of Medicine

Publication Details

Hardcover / 280 pages

ISBN: 9781641770460

Available: 6/25/2019

- Media: Request a Review Copy

- Academia: Request an Exam Copy

About the Author

Theodore Dalrymple is a retired physician and psychiatrist. He is a contributing editor of City Journal and frequent contributor to the London Spectator, The New Criterion, and other leading magazines and newspapers.

Praise

Excerpt

Most doctors read medical journals for guidance in their practice and assume that the summary and conclusions at the end of articles are more or less justified by what goes before. After all, medical journals have editors whose job it is not only to select articles worthy of inclusion but also to eliminate obvious error. For most of my career, I believed that they did their job.

This is the belief, too, of most journalists who relay the results of medical research to the general public as if they were incontestable. Of necessity, perhaps, journalists take the summary and conclusions of scientific papers at face value, having neither the time nor the inclination to inquire much further. A straightforward or unequivocal scientific fact is journalistically more compelling than is a still-unanswered question. Likewise, a doubling of the risk of a disease is a more dramatic story than the extreme unlikelihood of contracting the disease in the first place, even at double the risk – a small detail that medical journals often omit.

Since my retirement from medical practice, I have had time to read journals with much closer attention and have come to realize just how flawed much of their content is. One cannot take accuracy or even veracity for granted, irrespective of how many eminent editors are on the masthead of a journal. The responsibility for detecting error is the reader’s, and he must keep his mind open as much to what has been omitted as to what is included. Ever since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, one of the most famous medical authors of all time, recorded the exploits and dicta of Sherlock Holmes, we have been aware that the silence of the dog that did not bark may be as eloquent as any barking could be. The more carefully I read medical papers, the more often the dog that did not bark in the nighttime seems to me an important lesson. What is not said is often very revealing, especially to suspicious minds like mine has become.

I was encouraged to write this book after my nephew Joseph, who is a medical student in Paris, asked my help before the examination that he was about to take in the proper, critical way to read a medical research paper. I was never taught this and wish that I had been. In trying to help him, I clarified my own ideas.

The causes of error are multitudinous, and range from carelessness to dishonesty, from wishful thinking to outright corruption, with everything in between. Medical research relies on ever-more-complex statistics to conclude anything at all, and common sense is often the first victim of technical sophistication. But there is no such thing as a perfect paper that omits nothing, answers all possible questions and cannot be criticized on any ground.

In the following pages, I examine the contents of the New England Journal of Medicine over the course of a year. Along with the Lancet, it is the most important and influential general medical journal in the world. When it pronounces on social philosophy, as it often does, it reads like Pravda, not in the sense that it is Marxist-Leninist, of course, but in the sense that it takes its own attitudes so much for granted, as being so indisputably virtuous and true, that other viewpoints are rarely if ever expressed in its pages. The Journal is certainly not alone in this regard: the Lancet is, if anything, worse. The dead hand of political correctness is upon medical journals.

My object has been twofold: first, to alert readers to the sickly self-righteousness that seems to me to have infected the New England Journal of Medicine, contracted no doubt from the wider culture; and second, to attune them to the ambiguities of the medical research that is so often taken to provide unequivocal answers, even to questions that are inescapably ethical in nature. It is not my wish to hold up anyone to ridicule or contempt, which is why I have omitted the names of authors, and only occasionally have inferred or ascribed motives when they seemed obvious to me.

I begin with the issue of January 12, 2017, because my annual subscription started on this date, and proceed week by week through January 4, 2018. My hope is that readers will come to see how complex and difficult medical research is, and how they should remain skeptical of medical findings reported in the general media.