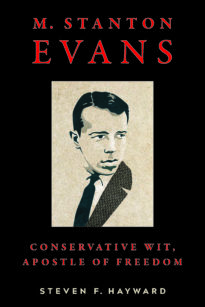

Acompact car with a few books, an electric typewriter, my few days into the new year in January 1981, I loaded up my Gerald Ford–era three-piece suit, two sport coats, and whatever remaining presentable clothing I owned and struck out from my family home in suburban Los Angeles for Washington, DC. I was taking up as an intern for M. Stanton Evans at his recently established National Journalism Center. Although the formal program only lasted twelve weeks, it turned out to be a decisive, life-altering journey.

The context of that moment helps in appreciating fully the intellectual and political portrait that follows. I had graduated from college the previous spring and spent the summer backpacking around Europe and the fall lounging around my parents’ spacious house like Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate (which was actually set in my home town in the novel) looking for a job in a tough market for recent graduates. I didn’t turn up much beyond a couple of sketchy entry-level sales prospects. I really wanted to be a writer or journalist but had no idea how to go about starting such a career.

So my eyes perked up when I spotted a small classified ad in National Review about internships at the National Journalism Center (hereafter NJC). Twelve weeks, lodging, and $100 a week! Interest became excitement when I focused on the fact that M. Stanton Evans was the impresario of NJC. I was familiar with Evans’s writing through his syndicated column that amazingly appeared in the Los Angeles Times (I was such a nerd as a teen that I read the Times op-ed page before the sports page every morning), but I was also familiar with him from his articles in Human Events and National Review as I subscribed to both. The most distinct impression, however, came from hearing his brief radio commentaries for CBS News’s “Spectrum” series, which I’d heard as a teen when driving around with my father, who listened exclusively to news radio. More than once I recall reaching a destination but remaining in the car to hear the end of Stan’s commentary. Along with the cogency and seriousness of his commentaries, what most struck me about Evans was his deep baritone voice. His best friend and fellow journalist, Ralph Bennett of Reader’s Digest, ably described Evans as having “an enviably sonorous voice, with a finely civilized gravel to it. There was a whisper of Texas, Tennessee, and tobacco. It has that flat timbre of the Midwest, and a hint of Mississippi in the exit when he was relaxed and talking about basketball or rock and roll.”

The opening weeks of 1981 coincided with the arrival of Ronald Reagan to begin the Reagan Revolution. Anyone who came of age in the late 1970s, when the conservative intellectual movement was alive with fertile creativity and new expression, couldn’t help but sense the building critical mass that culminated in Reagan’s landslide election. To paraphrase Wordsworth, “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive/But to be a young conservative was very heaven.” The more so in the company of similarly situated young conservatives starting out in the world—fellow NJC interns in my class included John Fund, Martin Morse Wooster, and John Barnes—under the tutelage of one of the key figures in the conservative movement.

The first thing you learned about Stan Evans upon meeting him was his genuine warmth and casual friendliness. There was nothing standoffish or elitist about this highly accomplished, Phi Beta Kappa, Yale-educated man. In fact “elitist” is the last adjective you’d ever attach to Stan Evans. In those days he seldom wore a conventional business suit or necktie, though he did own a tie that played the University of Indiana fight song. Stan preferred more casual attire, especially turtlenecks, going directly against the competitive sartorial conventions of Washington, which has the strictest dress code this side of Starfleet Academy. Daniel Oliver called Evans “everyman’s Bill Buckley.” One of his most famous quotes was his summary of how his thinking was the same as the farmer you’d find in Seymour, Indiana.

If you only knew Stan Evans through his newspaper column, radio commentaries, or books, you had no idea how darn funny he was. Had he not been a serious man, he could have had a career as a stand-up comic. He fully internalized Churchill’s axiom that “a joke is a very serious thing.” As with brand-name comics taking the stage, you smiled and suppressed a laugh before he began speaking. “M. Stanton Evans had only to stand before a microphone to bring smiles to an expectant conservative audience,” Lee Edwards recalls. The libertarian legal scholar Roger Pilon said, “Whoever said conservatives were no fun didn’t know Stan.”