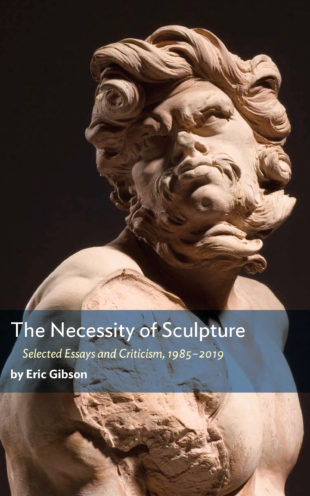

The Necessity of Sculpture brings together a selection of articles on sculpture and sculptors from Eric Gibson’s nearly four-decade career as an art critic. It covers subjects as diverse as Mesopotamian cylinder seals, war memorials, and the art of the American West; stylistic periods such as the Hellenistic in Ancient Greece and Kamakura in medieval Japan; Michelangelo, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and other historical figures; modernists like Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, and Alberto Giacometti; and contemporary artists including Richard Serra, Rachel Whiteread, and Jeff Koons. Organized chronologically by artist and period, this collection is as much a synoptic history of sculpture as it is an art chronicle. At the same time, it is an illuminating introduction to the subject for anyone coming to it for the first time.

Free shipping on all orders over $40

The Necessity of Sculpture

Selected Essays and Criticism, 1985–2019

Also Purchase as e-Book

Publication Details

Paperback / 256 pages

ISBN: 9781641771085

Available: 3/3/2020

- Media: Request a Review Copy

- Academia: Request an Exam Copy

About the Author

Eric Gibson is the Arts in Review editor of The Wall Street Journal and one of the paper’s art critics. He grew up in England and graduated with a B.A. in Art History from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. He is the author of The Sculpture of Clement Meadmore (Hudson Hills Press, 1993) and lives with his wife on Long Island.

Praise

Excerpt

For admirers of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), or even of sculpture generally, the collection of fifteen of his terracotta sketches in the Fogg Art Museum has long been a pilgrimage point to glean a deeper insight into his genius, or simply a straightforward Bernini fix. If the essence of his marbles is their jaw-dropping illusionism – their ability to simulate wind-blown hair, soft flesh, even tears – what distinguishes these preparatory works is their immediacy. They convey the quick flash of an idea and even, in their rough tooling or the vestigial impress of a finger, the very presence of the artist. Now the Metropolitan and Kimbell museums have joined forces to present a larger and more representative group of these clay sketches and related drawings. It is a stunning show, and without exaggeration, for the way it enlarges and even transforms our understand-ing of Bernini, one of the most important accorded any artist in our time.

“Bernini: Sculpting in Clay” was organized by a team of four curators: Ian Wardropper, currently director of the Frick Collection and before that chairman of the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts department at the Met; Anthony Sigel, conservator of objects and sculpture at the Harvard Art Museums; C. D. Dickerson III, curator of Euro-pean art at the Kimbell; and Paola D’Agostino, senior research associate at the Met. They have assembled thirty-nine modelli and bozzetti from public and private collections around the world and installed them with wall photos of the completed projects in Rome for which they were conceived. Considering how delicate they are – some, such as a “St. Longinus” sketch from the Museo di Roma, are in such fragmentary condition they could be mistaken for semi-abstract works by contemporary ceramic artists like Stephen de Staebler or Mary Frank – it is a tribute to the industry and perseverance of the curators, not to mention the generosity of the lenders, that this exhibition came to fruition. It will probably never be done again. It is a once-in-a-lifetime event.

The earliest work in the show is Charity with Four Children (ca. 1627), an allegorical group planned for the tomb of Pope Urban VIII. The show concludes with studies of angels for Bernini’s last commission, the 1672 Altar of the Blessed Sacrament in St. Peter’s Basilica. In between, virtually all aspects of his output are represented, among them the Four Rivers and Moor fountains, the Cornaro Chapel, equestrian portraits of Constantine and Louis XIV, and the Cathedra Petri. It amounts to a kind of synoptic retrospective, and as such the byways can be as captivating as the main thoroughfare. One of the most irresistible objects in the entire show is the model for the Lion on the Four Rivers Fountain. The King of Beasts is but a bit player in the completed project; you see only his head reaching down to lap at the pool-ing water, and his hind parts. Yet Bernini treats the model as if it were the main event, giving us a finely detailed, richly textured representation that is as closely observed and as penetrating a characterization as any of his human portraits.