Harry V. Jaffa (1918–2015), professor at Claremont McKenna College and distinguished fellow of the Claremont Institute, was one of the most influential thinkers of the twentieth century. His hundreds of students have reached positions of power and prestige throughout the intellectual and political world, including at the Supreme Court and the Trump White House.

Jaffa authored Barry Goldwater’s famous 1964 Republican Convention speech, which declared, “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” William F. Buckley, Jaffa’s close friend and a key figure in shaping the modern conservative movement, wrote, “If you think it is hard arguing with Harry Jaffa, try agreeing with him.” His widely acclaimed book Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates (1959) was the first scholarly work to treat Abraham Lincoln as a serious philosophical thinker.

As the earliest protégé of the controversial scholar Leo Strauss, Jaffa used his theoretical insights to argue that the United States is the “best regime” in principle. He saw the American Revolution and the Civil War as world-historical events that revealed the true nature of politics. Statesmanship, constitutional government, and the virtues of republican citizenship are keys to unlocking the most important truths of political philosophy.

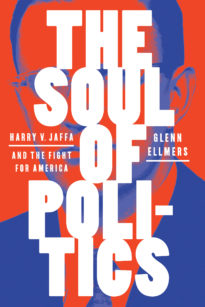

Jaffa’s student, Glenn Ellmers, was given complete access to Jaffa’s private papers at Hillsdale College to produce the first comprehensive examination of his teacher’s vast body of work. In addition to Lincoln and the founding fathers, the book shares Jaffa’s profound insights into Aristotle, William Shakespeare, Winston Churchill, and more.