In the aftermath of the murders of five Dallas police officers and the recent fatal shootings of black men by police in Louisiana, Minnesota and New York—and the videos of those events—we are hearing renewed calls for a “national conversation” on race and policing.

While the “conversation” called for by the Obama White House and our media—in particular with respect to criminal justice—tends to be curiously one-sided, a real good faith effort to examine such issues would begin by fairly examining the empirical evidence.

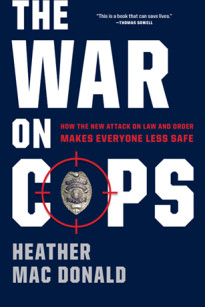

In Heather Mac Donald’s The War On Cops, we have a work that catalogues and engages with just such data. And while, as the title suggests, Mac Donald challenges the Left’s narrative of a systemically racist criminal justice system, the book provides the relevant evidence around which any intellectually honest conversation would have to revolve.

Below are 11 passages drawn directly from Mac Donald’s book that highlight the salient data on race and crime in America.

Or for the cliff’s notes, you can listen to my in-depth interview with Mac Donald below:

i

1) On black victims of fatal police shootings

The Washington Post found press documentation of 258 black victims of fatal police shootings in 2015, most of whom were seriously attacking the officer. In 2014, the most recent year for which such data are available, there were 6,095 black homicide victims in the United States, which means that the police could eliminate all of their own fatal shootings without having a significant impact on the black homicide death rate. The killers of those black homicide victims are overwhelmingly other blacks—who are responsible for a death risk ten times that of whites in urban areas. Blacks are killed by police at a lower rate than their threat to officers would predict. To cite more data on this point: in 2013, blacks made up 42 percent of all cop-killers whose race was known, even though blacks are only about 13 percent of the nation’s population. Little over a quarter of all homicides by police involve black victims.

2) On black versus white victims of fatal policing shootings

The [New York] Times trotted out the misleading statistic published by ProPublica in October 2014 that young black males are 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than are young white males—a calculation that overlooks the fact that young black men commit homicide at nearly ten times the rate of young white and Hispanic males combined.* That astronomically higher homicide-commission rate means that police officers are going to be sent to fight crime disproportionately in black neighborhoods, where they will more likely encounter armed shooting suspects…Asians are minorities, which, according to the Times’ ideology, should make them the target of police brutality. But they barely show up in police-shooting data because their crime rates are so low.

For the period 2005–09, a significant portion of victims in the ProPublica study—62 percent—were resisting arrest or assaulting an officer, as Michael Brown did.

3) More on victims of fatal police shootings

[F]or 2015, the Post documented 987 victims of fatal police shootings, about twice the number historically recorded by federal agencies. Whites were 50 percent of those victims, and blacks were 26 percent.

That percentage of black victims is not helpful in proving that policing is racist. Though blacks are 13 percent of the nation’s population (and whites, 62 percent), blacks’ violent crime rates would predict that at least a quarter of the victims of police killings would be black. Police shootings will be correlated with the prevalence of armed suspects, violent crime, and suspect resistance in a population and area. Blacks were charged with 62 percent of all robberies, 57 percent of all murders, and 45 percent of all assaults in the 75 largest U.S. counties in 2009, while constituting roughly 15 percent of the population in those counties. From 2005 to 2014, 40 percent of cop-killers were black. Given the racially lopsided nature of gun violence, a 26 percent rate of black victimization by the police is not evidence of bias.

Moreover, the vast majority of the 258 black victims of police shootings in 2015 were armed, as were white and Hispanic victims. And 258 is a small fraction of the nearly 6,000 annual black victims of black committed homicide. Indeed, the percentage of black homicide deaths that result from police killings is far less than the percentage of white and Hispanic homicide deaths that result from police killings: 4 percent of black homicide victims are killed by the police, compared with 12 percent of white and Hispanic homicide victims. A “Lives Matter” antipolice movement, if there is to be one, would more appropriately be labeled “White and Hispanic Lives Matter.”

4) On crime rates by race

Black made up 60.5 percent of all murder arrests in Missouri in 2012 and 58 percent of all robbery arrests, though they are less than 12 percent of the state’s population. Such vast disparities are found in every city and state in the country; there is no reason to think that Ferguson is any different…New York City is typical: blacks are only 23 percent of the population but commit over 75 percent of all shootings in the city, as reported by the victims of and witnesses to those shootings; whites commit under 2 percent of all shootings, according to victims and witnesses, though they are 33 percent of the city’s population. Blacks commit 70 percent of all robberies; whites, 4 percent. The black-white crime disparity in New York would be even greater without New York’s large Hispanic population. Black and Hispanic shootings together account for 98 percent of all illegal gunfire. Ferguson has only a 1 percent Hispanic population, so the contrast between the white and black shares of crime is starker there.

5) On whether people of different races are treated differently by the criminal justice system

“Racial differences in patterns of offending, not racial bias by police and other officials, are the principal reason that such greater proportions of blacks than whites are arrested, prosecuted, convicted and imprisoned,” concluded Michael Tonry, a criminologist, in his book Malign Neglect (1995). A Justice Department survey of felony cases from the country’s 75 largest urban areas, conducted in 1994, found that blacks had a lower chance of prosecution following a felony than whites, and were less likely to be found guilty at trial. Blacks were more likely to be sentenced to prison following a conviction, but that result reflected their past crimes and the gravity of their current offense…

In Cleveland, homicides for 2015 increased by 90 percent over the previous year. Through the end of April 2015, shootings in St. Louis were up 39 percent, robberies 43 percent, and homicides 25 percent. Murders in Nashville rose 83 percent in 2015; Milwaukee closed out the year with a 72 percent increase in homicides. Shootings in Chicago had increased 24 percent and homicides 17 percent by May 2015; that surge continued into 2016, with more than 100 Chicagoans shot in the first ten days of the new year, a threefold increase from the same period in 2015. Washington, D.C., ended 2015 with a 54 percent increase in murders; Minneapolis was up 61 percent in homicides. This ongoing crime spike is a stark contrast to the 20-year trend of increasing public safety that continued into the middle of 2014, and cities with large black populations have been hit the hardest…Crime dropped 50 percent nationally over the last two decades, and it would be highly unusual to give back all that gain in just one year. But a 16 percent homicide increase in at least 60 major cities is startling enough.

7) On the risks to police officers from black assailants versus the risks to unarmed blacks by police officers

Further analysis of the [Washington] Post’s data reveals that police officers are at greater risk from blacks than unarmed blacks are from police officers. Even if we accept the Post’s typology of “unarmed” victims at face value, the per capita rate of officers being feloniously killed is 45 times higher than the rate at which unarmed black males are killed by cops. And an officer’s chance of getting killed by a black assailant is 18.5 times higher than the chance of an unarmed black getting killed by a cop.

8) On incarceration rates versus crime rates

In 2006, blacks were 37.5 percent of all state and federal prisoners, though they’re under 13 percent of the national population. About one in 33 black men was in prison in 2006, compared with one in 205 white men and one in 79 Hispanic men. Eleven percent of all black males between the ages of 20 and 34 are in prison or jail. The dramatic rise in the prison and jail population over the previous three decades—to 2.3 million people at the end of 2007—amplified the racial accusations against the criminal-justice system.

…In 2005, the black homicide rate was over seven times the rate of whites and Hispanics combined, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. From 1976 to 2005, blacks committed over 52 percent of all murders in America. In 2006, the black arrest rate for most crimes was two to nearly three times blacks’ representation in the population. Blacks constituted 39.3 percent of all violent-crime arrests, including 56.3 percent of all robbery and 34.5 percent of all aggravated-assault arrests, and 29.4 percent of all property-crime arrests. The arrest data in 2013 were virtually the same.

9) On differences in criminal sentencing by race

In 1997, criminologists Robert Sampson and Janet Lauritsen reviewed the massive literature on charging and sentencing. They concluded that “large racial differences in criminal offending,” not racism, explained why more blacks were in prison proportionately than whites and for longer terms. A 1987 analysis of Georgia felony convictions, for example, found that blacks frequently received disproportionately lenient punishment. A 1990 study of 11,000 California cases found that slight racial disparities in sentence length resulted from blacks’ prior records and other legally relevant variables. A 1994 Justice Department survey of felony cases from the country’s 75 largest urban areas…discovered that blacks actually had a lower chance of prosecution following a felony than whites did and that they were less likely to be found guilty at trial. Following conviction, blacks were more likely to receive prison sentences, however—an outcome that reflected the gravity of their offenses as well as their criminal records.

The media’s favorite criminologist, Alfred Blumstein, found in 1993 that blacks were significantly underrepresented in prison for homicide compared with their presence in the arrest data.

10) On the impact of drug laws on incarceration rates

[E]ven during the most rapid period of prison population growth—from 1980 to 1990—36 percent of the growth in state prisons (where 88 percent of the nation’s prisoners are housed) came from violent crimes, compared with 33 percent from drug crimes. Since then, drug offenders have played an even smaller role in state prison expansion. Violent offenders accounted for 53 percent of the census increase from 1990 to 2000, and all of the increase from 1999 to 2004.

Next, critics blame drug enforcement for rising racial disparities in prison. Again, the facts say otherwise. In 2006, blacks were 37.5 percent of the 1,274,600 state prisoners. If you remove drug prisoners from that population, the percentage of black prisoners drops to 37 percent—half a percentage point, hardly a significant difference. (No criminologist, to the best of my knowledge, has ever performed this exercise.)

The rise of drug cases in the criminal-justice system has been dramatic, it’s important to acknowledge. In 1979, drug offenders were 6.4 percent of the state prison population; in 2004, they were 20 percent. Even so, violent and property offenders continue to dominate the ranks: in 2004, 52 percent of state prisoners were serving time for violence and 21 percent for property crimes, for a combined total over three and a half times that of state drug offenders. In federal prisons, drug offenders went from 25 percent of all federal inmates in 1980 to 47.6 percent of all federal inmates in 2006. Drug-war opponents focus almost exclusively on federal rather than state prisons because the proportion of drug offenders is highest there. But the federal system held just 12.3 percent of the nation’s prisoners in 2006.

11) On racial disparities in incarceration rates

[T]he racial disparity in incarceration rates has shrunk by nearly a quarter since 2000, with the black incarceration rate down 22 percent and the white incarceration rate up 4 percent. A 2011 study of California and New York arrest data led by Darrell Steffensmeier, a criminologist at Pennsylvania State University, found that blacks commit homicide at 11 times the rate of whites and robbery at 12 times the rate of whites. Such disparities are repeated in city-level data. In the 75 largest county jurisdictions in 2009 (as noted in Chapter 13), blacks were 62 percent of robbery defendants, 61 percent of weapons offenders, 57 percent of murder defendants, and 50 percent of forgery cases, even though blacks are less than 13 percent of the national population. They dominated the drug-trafficking cases more than possession cases. Blacks made up 53 percent of all state trafficking defendants in 2009, whites made up 22 percent, and Hispanics 23 percent, whereas in possession prosecutions, blacks were 39 percent of defendants, whites 34 percent, and Hispanics 26 percent.

Repeated efforts by criminologists to find a racial smoking gun in the criminal-justice system have come up short.

The most heartrending statistic of all from Mac Donald’s The War On Cops may be this one: “Black males between the ages of 14 and 17 die from shootings at more than six times the rate of white and Hispanic male teens combined, thanks to a ten times higher rate of homicide committed by black teens.”

Mac Donald’s antidote seems eminently more reasonable than those being presented by our political leaders:

Until the black family is reconstituted, the best protection that the law-abiding residents of urban neighborhoods have is the police. They are the government agency most committed to the proposition that “black lives matter.” The relentless effort to demonize the police for enforcing the law can only leave poor communities more vulnerable to anarchy.

For more, read The War on Cops and listen to my in-depth interview with Heather Mac Donald.