In the nearly two years following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO, charges of racism in law enforcement have galvanized our media and cultural discourse. At the same time, violence—and black on black crime in particular—has soared in American cities. We recently asked Heather Mac Donald, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor to City Journal, to discuss these issues and her new book, The War on Cops.

Are cops racist?

I wrote The War on Cops to rebut that dangerous lie: that policing, and indeed the entire criminal justice system, are racist. That lie threatens the record-breaking national crime drop of the last two decades by discouraging cops from doing their jobs. The attack on the criminal justice system distracts attention from the real law enforcement problem in urban America: elevated rates of black-on-black crime.

I wrote The War on Cops to rebut a dangerous lie: that policing, and indeed the entire criminal justice system, are racist.

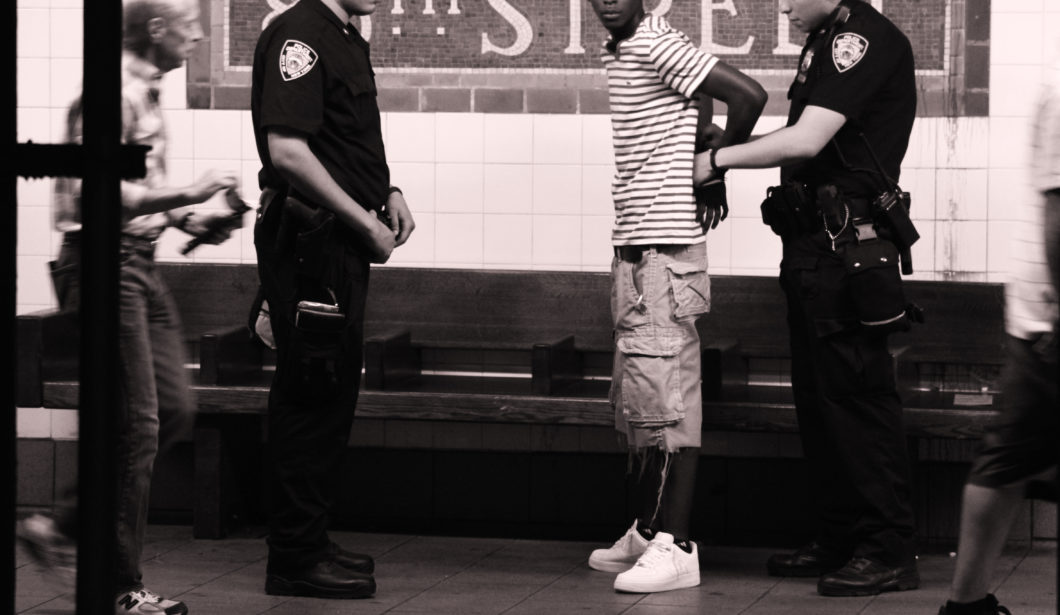

You argue that proactive policing has been the greatest public policy success story of the last quarter century. How have controversial policing tactics such as “stop, question, and frisk” and “broken windows” policing contributed to massive drops in crime?

“Stop, question, and frisk” and “broken windows” policing avert serious crime before it happens. In the case of “stop, question, and frisk,” officers are asked to use their knowledge of local crime conditions to intervene in suspicious situations before someone has been victimized. If a neighborhood has experienced a series of car thefts, for example, and an officer sees someone walking along a row of parked cars trying their door handles, the officer may stop that person to find out what he is doing. Criminals have acknowledged that the chance of being stopped deters them from carrying guns on their person.

“Broken windows” policing targets public disorder that signals that informal social controls in an area have broken down. Accosting someone who is drinking whiskey outside a bodega at 3 pm may stop a stabbing at 10 pm that night, after the drinker is drunk. Pedestrian stops and broken windows enforcement were a major part of the 1990s policing revolution that brought safety to millions of urban residents.

In The War on Cops, you give voice to the residents of high-crime neighborhoods who support proactive policing. How have data-driven, accountable police departments actually saved and improved the lives of minorities in America?

The greatest beneficiaries of proactive policing and the resulting crime drop have been minorities. In New York City alone, over 10,000 minority males are alive today who would have been dead had crime rates remained at their early 1990s levels. The reduction of crime in inner-city neighborhoods has allowed their law-abiding residents the basic freedoms that residents of safer neighborhoods take for granted: being able to sleep in your bed rather than your bathtub without fear of getting shot, for example. The drop in crime encouraged businesses to set up shop in previously drug-infested areas, providing residents with greater consumer options and more job opportunities. Public safety is the precondition for urban regeneration; as long as crime rates remain high, economic activity in an area will be suppressed.

In New York City alone, over 10,000 minority males are alive today, who would have been dead had crime rates remained at their early 1990s levels.

You introduced the idea of the “Ferguson effect” into the public discourse. Can you briefly explain what this is and how it threatens the safety of citizens?

The “Ferguson effect” refers to the twin phenomena of officers backing off of proactive policing under the relentless charge that they are racist, and the resulting emboldening of criminals. Since the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in August 2014, the Black Lives Matter movement has controlled the public discourse about law enforcement and the media have parroted the movement’s claim that police officers regularly gun down unarmed black males with impunity. Officers in urban areas now worry about becoming the latest racist cop of the week on CNN if their justified use of force against a resisting suspect is distorted by an incomplete cell phone video. As a result, officers are doing less proactive policing and crime is shooting through the roof in urban neighborhoods. In 2015, homicides in the largest 50 cities rose nearly 17%, the largest one-year rise in murder in over two decades. Homicides in Baltimore reached their highest per capita rate in the city’s history last year.

The rate of murdered police officers is over 200% higher than it was at this time last year. Is this an anomaly or has there been a significant increase in hostility towards law enforcement?

There has been a huge increase in hostility towards law enforcement in urban areas; suspects are violently resisting arrest, bystanders routinely jeer when cops get out of patrol cars. The BLM claim that cops are racist murderers has led to the assassination and attempted assassination of police officers. Any increase in attacks on law enforcement bears watching because such violence threatens the very existence of law and order.

In 2015, homicides in the largest 50 cities rose nearly 17%, the largest one-year rise in murder in over two decades.

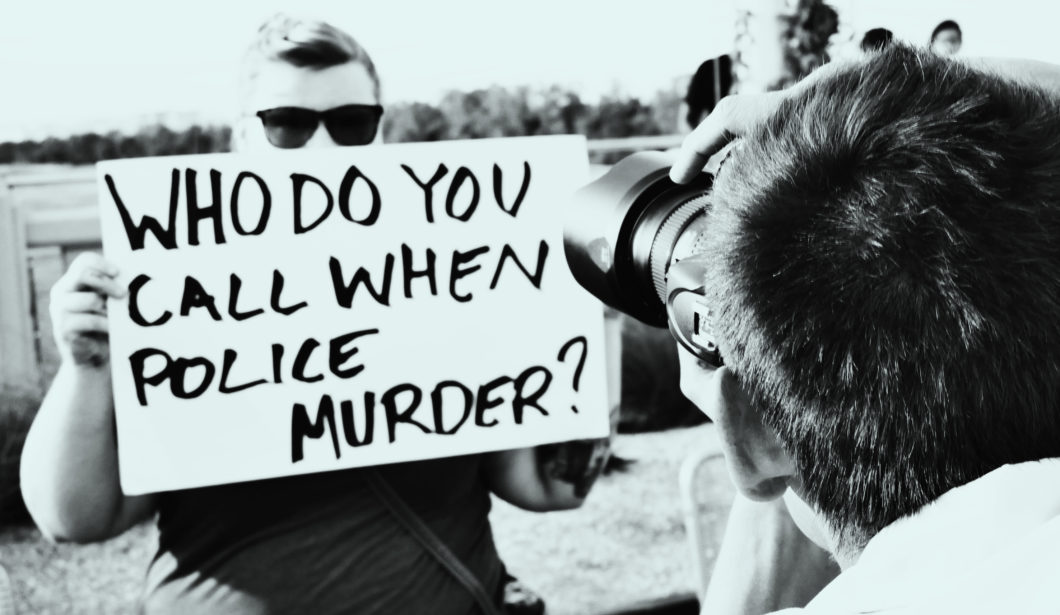

Is there a legitimate claim about widespread use of police brutality against minorities?

Police brutality must be prevented and eradicated wherever it happens. But it is not true that there is a widespread problem of police brutality in minority neighborhoods or that police shootings are driven by race. Police shootings of blacks are much lower than what black crime rates would predict. And police shootings comprise a much lower proportion of black homicide deaths than white and Hispanic homicide deaths. The police shoot very few unarmed individuals each year, and most of those individuals were trying to grab the officer’s gun or violently resisting arrest. Meanwhile, nearly 6,000 blacks are murdered each year, overwhelmingly by other blacks, and the press looks the other way.

Aren’t African Americans at greater risk for arrest, prosecution, and longer prison sentences for drug crimes than whites?

Blacks’ risk of prosecution for drug crimes is based on their involvement in drug trafficking, not on their race. Police enforce drug laws where citizens are begging for drug enforcement and that is in minority neighborhoods. Study after study has shown that blacks’ overrepresentation in prison is due to their higher rates of crime and more extensive criminal histories, not to phantom racism within the criminal justice system. Nor is blacks’ overrepresentation in prison due to the enforcement of drug laws. If all drug prisoners were removed from state prisons—which house 87% of the nation’s prisoners—blacks’ proportion of state prisoners would be unchanged.

Nearly 6,000 blacks are murdered each year, overwhelmingly by other blacks, and the press looks the other way.

What do you say to calls for criminal justice reforms that would weaken criminal penalties and reduce incarcerations?

America is not overincarcerating. Only 3% of all violent felons and property offenders end up in prison. The longer and more certain sentences for repeat felons instituted in the late 1970s and 1980s played a major part in the subsequent crime drop. While there is nothing sacrosanct about any particular legislated sentence length, the cumulative assault on every aspect of the criminal justice system—from traffic laws to warrant enforcement to sentencing policy—is a dangerous trend. Even more dangerous is the conceit driving that assault: that the criminal justice system is racist.

How can we repair the current attitude towards police?

The police can always benefit from more training in courtesy and respect. But they cannot succeed in repairing frayed community relations so long as the propaganda campaign being waged against cops continues unabated. Members of the press need to talk to those many residents of high-crime neighborhoods who want more police officers safeguarding their communities. The media also need to break the taboo regarding black crime. As long as the public remains ignorant about the vast racial disproportion in violent crime commission, people will be susceptible to the lie that the police are in minority neighborhoods to oppress, rather than to save lives.