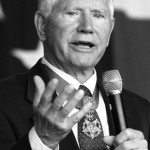

Leo Thorsness (February 14, 1932 – May 2, 2017) received his Medal of Honor after he was released from his North Vietnamese prison in 1973. From 1988 to 1992, he served as a senator from Washington State.

Free shipping on all orders over $40

Sunday morning at the Hanoi Hilton was church time. To gather our “congregation,” the Senior Ranking Officer (SRO) tapped“CC,” quietly on his wall. Each cell in turn tapped “CC,” and soon all have been alerted to Church Call. The service was a prayer and a reciting of Bible verses. If I was lucky, I was in a cell with one or two other POWs, and we could pool our knowledge of the Bible.

A failed rescue attempt led to the most memorable of our church experiences. It happened on November 20, 1970, when U.S. Special Forces staged a mission to rescue the POWs believed to be at Son Tay, one of the small prisons the North Vietnamese maintained outside Hanoi. The raid was brilliantly planned and executed perfectly. Our men landed at the prison in helicopters and came home without the loss of a single American. There was only one problem: all the POWs had been moved out of Son Tay about four months before the rescue effort so none of us went back with our rescuers.

The mission still turned out to be a huge success for us, however. Realizing that such rescue attempts could happen again, the North Vietnamese brought us in from outlying prison camps into the main Hoa Lo prison in Hanoi: the Hanoi Hilton. Within hours of the raid, we were moved into large cells—43 of us in my cell.

It was the greatest day of our prison life. For the first time, we were meeting POWs whose names we had memorized years earlier. Many of us had formed intense friendships through the tap code with men we’d never seen. As we met that night, “So this is what you look like” was heard over and over throughout the cell. We compared our treatment, and it seemed important to each of us to tell one another of our torture experiences. I’ve never seen more empathy in anyone’s eyes than when telling a fellow POW about being tortured. We each needed to tell our torture story—once. We never told them again to the same POW.

The handshakes, back slapping, and bear hugs went on and on. Some of us had been tortured for the protection or benefit of a “tap-code buddy.” Now there was love and respect to be repaid. No one slept that first night; too much joy, excitement, and talk.

The next morning, we needed to determine the SRO. The highest rank in our cell was O-4, which is a major. (“O” stands for officer, so O-1 is second lieutenant or ensign, O-2 first lieutenant, O-3 captain, O-4 major, O-5 lieutenant colonel, O-6 colonel, O-7 brigadier general, and on up to O-10 for a four-star general.) We put all the O-4s together and then compared the date when the rank was attained and arrived at a hierarchy. We did the same with the O-3s, the O-2s, and the O-1s. When we were done, all 43 of us knew exactly where we stood in the command structure. Our SRO turned out to be Ned Shuman—a really good Naval aviator.

The first Sunday in the large cell, someone said, “Let’s have church service.” Good idea, we all agreed. One POW volunteered to lead the service, and we started gathering in the other end of the long rectangular cell from the cell door. No sooner had we gathered than an English-speaking Vietnamese officer who worked as an interrogator burst into the cell with a dozen armed guards. Ned Shuman went to the officer and said there wouldn’t be a problem; we were just going to have a short church service.

The response was unyielding: we were not allowed to gather into groups larger than three persons and we absolutely could not have a church service.

During the next few days we all grumbled that we should not have backed down in our intention to have a church service and ought to do it the coming Sunday. Toward the end of the week, Ned stepped forward and said, “Are we really committed to having church Sunday?”

There was a murmuring of assent throughout the cell.

Ned said, “No, I want to know person by person if you are really committed to holding church.”

We all knew the implications of our answer: If we went ahead with the plan, some would pay the price—starting with Ned himself because he was the SRO. He went around the cell pointing to each of us individually. “Leo, are you committed?” “Yes.” Ned then moved to Jim and asked the same question. “Yes,” Jim responded. And so on until he had asked each of us by name.

When the 42nd man said yes, it was unanimous. We had 100 percent commitment to hold church next Sunday. At that instant, Ned knew he would end up in the torture cells at Heartbreak.

It was different from the previous Sunday. We now had a goal, and we were committed. We only needed to develop a plan.

Sunday morning came, and we knew they would be watching us again. Once more, we gathered in the far end of the cell. As soon as we moved together, the interrogator and guards burst through the door. Ned stepped forward and said there wouldn’t be a problem: We were just going to hold a quiet ten-minute church service and then we would spread back out in the cell. As expected, they grabbed Ned and hauled him off to Heartbreak for torture.

Our plan unfolded. The second ranking man, the new SRO, stood, walked to the center of the cell and in a clear firm voice said, “Gentlemen,” our signal to stand, “the Lord’s Prayer.” We got perhaps halfway through the prayer, when the guards grabbed the SRO and hauled him out the door toward Heartbreak.

As planned, the number three SRO stood, walked to the center of the cell, and said, “Gentlemen, the Lord’s Prayer.” We had gotten about to “Thy Kingdom come” before the guards grabbed him. Immediately, the number four SRO stood: “Gentlemen, the Lord’s Prayer.”

I have never heard five or six words of the Lord’s Prayer—as far as we got before they seized him—recited so loudly, or so reverently. The interrogator was shouting, “Stop, stop,” but we drowned him out. The guards were now hitting POWs with gun butts and the cell was in chaos.

The number five ranking officer was way back in the corner and took his time moving toward the center of the cell. (I was number seven, and not particularly anxious for him to hurry.) But just before he got to the center of the area, the cell became pin-drop quiet.

In Vietnamese, the interrogator spat out something to the guards, they grabbed number five SRO and they all left, locking the cell door behind them. The number six SRO began: “Gentlemen, the Lord’s Prayer.” This time we finished it.

Five courageous officers were tortured, but I think they believed it was worth it. From that Sunday on until we came home, we held a church service. We won. They lost. Forty-two men in prison pajamas followed Ned’s lead. I know I will never see a better example of pure raw leadership or ever pray with a better sense of the meaning of the words.