In M. Stanton Evans: Conservative Wit, Apostle of Freedom, Steven F. Hayward traces the life of the journalist, thinker, and political activist who shaped the modern conservative movement. As President of the American Conservative Union (ACU), M. Stanton Evans championed a Conservative third party while Americans floundered for political footing after Nixon’s resignation. He worked tirelessly from 1974-1976 to get Ronald Reagan elected on either the Republican nomination or the Conservative party’s first ticket. Though the third party never coalesced and Reagan didn’t succeed until 1980, Evans was instrumental in spreading awareness on the important differences between conservatives and Republicans that lend breadth to the conservative movement today.

—

As planning for the second Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in February 1975 proceeded, a new idea was gaining steam: abandoning the Republican Party and starting a new Conservative Party. At this early point in the 1976 election cycle, Reagan was being coy about his plans, and in any case it was thought difficult for Reagan or anyone else to dislodge Ford or Rockefeller from the GOP nomination if either chose to run. (Ford’s own intentions were still vague at the time.) National Review publisher William Rusher was the most vocal advocate of the idea, publishing in 1975 a book outlining the logic of the proposal, The Making of a New Majority Party. Rusher had in mind who should lead this new party: Reagan and Alabama Gov. George Wallace. Reagan would attract conservative Republicans, while Wallace would bring Democrats disaffected by the increasing social liberalism of the Democratic Party but who were, as yet, not much attracted to Republicans. Rusher met with Reagan to push the idea. Reagan was noncommittal, and he equivocated about the idea in the aftermath of the GOP wipeout at the polls in November, leaving open the possibility of a new third party in remarks to reporters just after the 1974 election. (Reagan privately disliked Wallace and didn’t like the idea of aligning with him.)

Evans, thoroughly disgusted with Republicans, was intrigued enough by the idea to write favorably about it in his new syndicated newspaper column in the fall of 1974 and make it a major focus of the CPAC February 1975 conference. (It may have been around this time that Evans first quipped that “It is a good thing Republican office holders are pro-life, since they spend so much time in the fetal position.”) The minutes of one December 1974 planning meeting records that ACU’s board concluded “that the conference resolve to appoint a New Party exploratory committee. It was felt that the conference must end on the note of ‘having taken a step; putting the conservative movement into a course of action.’ Mr. Evans’ suggestion that a ‘Committee for a New Majority’ result from the conference was approved in principle, as was the general use of this vehicle . . . prior to the establishment of a New Party.” More intriguing was Evans’s agreement to seek out a meeting with Gov. Wallace to pursue the idea.

The subsequent CPAC was sharply divided, and it debated the proposal vigorously, with many staunch conservatives arguing for it and others against. (One of the most vociferous opponents was the head of the College Republicans, a young Texan named Karl Rove.) A soundbite from Evans made the evening news broadcasts of both NBC and ABC: “I personally believe that in 1976 we need a new political party at the presidential level.” Evans told the roundtable panel at CPAC: “How one goes about doing that, what the options are in terms of candidates, these are things that need to be discussed. I realize, talking to my Republican friends, that this presents many terrible difficulties. This is not something to be lightly considered.”

In his after-action report on CPAC in Battle Line, Evans said accurately that “almost no one at the conference had much good to say for the Ford White House.” Only two Ford administration officials were even invited to CPAC: Treasury Secretary William Simon and Council of Economic Advisers chairman Alan Greenspan. Both declined. (One other detail of the second CPAC is worth including. Evans tried, unsuccessfully, to get Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whose recent snub by the Ford White House at Henry Kissinger’s urging further rankled conservatives, to speak at the second CPAC, enlisting Sen. Jesse Helms to help.)

…

Reagan, once again the headline speaker for the conference, walked a fine line that tilted toward his reservations with his now famous formulation about “no pale pastels” that he used throughout the late 1970s while still leaving the door slightly ajar:

Is it a third party that we need, or is it a new and revitalized second party, raising a banner of no pale pastels, but bold colors which make it unmistakably clear where we stand on all the issues troubling the people? . . . I do not believe I have proposed anything that is contrary to what has been considered Republican principle. It is at the same time the very basis of conservatism. It is time to reassert that principle and raise it to full view. And if there are those who cannot subscribe to these principles, then let them go their way.

Despite Reagan’s less than lukewarm treatment of the idea, he did not deter CPAC and ACU from setting in motion a serious third-party exploration and organizational effort, dubbed the Committee on Conservative Alternatives (COCA), with Sen. Jesse Helms as chairman. COCA contacted the secretaries of state for all fifty states about their third-party ballot access rules.

Evans understood that the third-party idea was dead unless Reagan led it. He wrote directly to Reagan in May 1975, attempting to persuade him that even if he won the Republican nomination in 1976, he would be saddled with the legacy of the Nixon-Ford failures and that at the very least Reagan should keep his thirdparty options open if he ran for the GOP nomination and lost. If the COCA effort went forward and qualified a party for the ballot, Reagan would have a ready-made structure in place.

Evans understood that the third-party idea was dead unless Reagan led it.

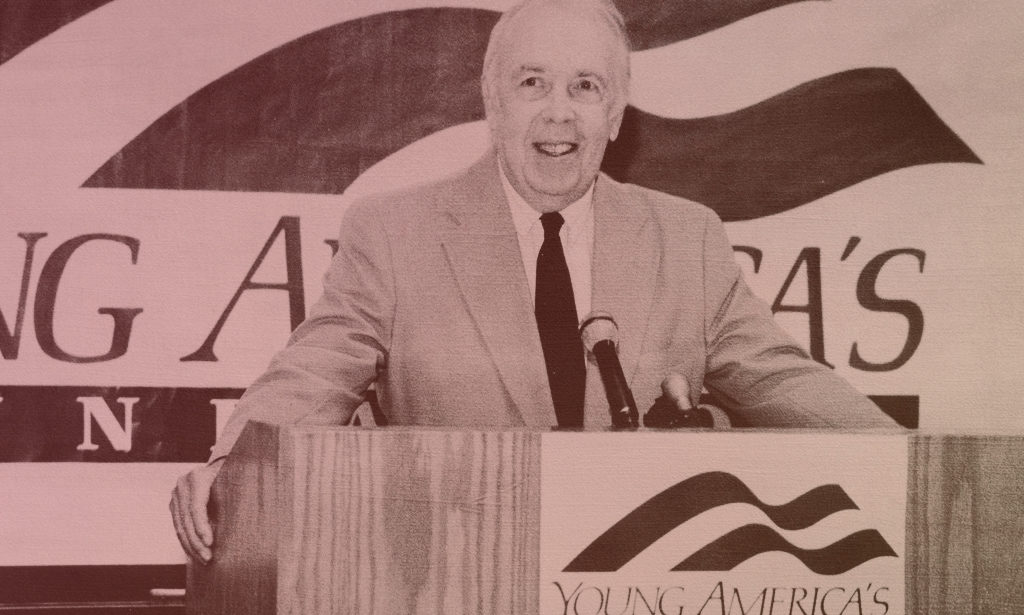

In August Evans and Rusher traveled to Alabama to feel out Wallace, who, Rusher biographer David Frisk wrote, “may not have known who they were.” Evans described the meeting to Frisk: “We were just getting to know him . . . Sort of an interview with him, to size him up, and he was very cordial to us.” Wallace remained aloof from the third-party effort as he was planning to (and did) run in the Democratic primaries in 1976. Evans came away favorable enough to write a positive column about his visit with Wallace. He described Wallace’s incipient presidential campaign as “the hottest political operation in the United States today . . . He is soft spoken, genial, earnest. One is not surprised that he made a good impression when he addressed the recent national convention of Young Americans for Freedom.” Evans concluded that Wallace represented a bona fide force on behalf of a conservative “new majority” in American politics.

—

Then, on November 4, 1975, Vice President Rockefeller announced that, at President Ford’s request, he would not be Ford’s running mate in 1976. There is little doubt that Ford relented to the pressure from conservatives; the fear of the imminent challenge from Reagan likely added to the decision. Speculation began immediately about who Ford might pick to replace Rockefeller, with names running the spectrum from liberal Republicans like Charles Percy all the way over to Reagan. In the end Ford picked Kansas Senator Bob Dole, who enjoyed a solid conservative reputation in his second term. But in the meantime, gaining Rockefeller’s ouster took more steam out of the third-party effort.

Speculation began immediately about who Ford might pick to replace Rockefeller... But in the meantime, gaining Rockefeller’s ouster took more steam out of the third-party effort.

As Reagan was gearing up to declare his candidacy, he provoked a major controversy with his controversial plan to cut the federal budget by $90 billion and transfer responsibilities for many programs directly to the states. It was a bold proposal, aiming at “cutting the Gordian knot” of federal dominance and stopping the flow of power and money to Washington. Today $90 billion is nearly a rounding error in a (normal, pre-COVID) federal budget of nearly $4 trillion, but in 1976 total federal spending was about $400 billion. Thus Reagan was proposing to cut the federal government by almost a quarter—but to cut federal taxes by the same amount (a key detail left out of much of the news coverage). The media—and the Ford campaign—savaged Reagan’s “radical” idea, arguing that it would lead to state tax increases and other horribles. The author of Reagan’s plan and the September speech that introduced it was former ACU employee Jeffery Bell, and even without that personal connection it was the kind of idea near to Evans’s heart, so naturally he mounted the barricades to defend it.

Evans wrote a long special supplement on “The Ronald Reagan Story” for Human Events in January 1976 that took up eight full pages (probably close to twelve thousand words). Having repeatedly called for articulate spokesmen for the conservative cause, Evans found his man in Reagan. After reviewing Reagan’s biography and record in Sacramento in some detail, Evans concluded that Reagan’s record as California governor paradoxically made him “more qualified to hold the office he seeks than is the man who currently occupies it.”

.

But the heart of the article was a spirited defense of Reagan’s devolution plan on the merits of long-familiar Evans themes about decentralized government and an extension of the political logic behind the new third-party idea. Like the third-party agitation, Reagan’s shadow over Ford was pushing Ford to the right: “First, it simply isn’t true that Ford is as conservative as Reagan, or even that Ford as President has generally been on the conservative side. And second, to the extent that Ford these days is perceived as a conservative, it is apparent on analysis that his conservatism is chiefly traceable to—Ronald Reagan . . . On balance, it seems rather plain that Reagan could make a considerably stronger run for the White House in the fall than could President Ford.” Above all, Evans argued that Reagan was the only Republican who could preempt another potential third-party bid by Wallace—unless that third-party bid consisted of Reagan and Wallace together. He took directly after the pundits and analysts who thought a Reagan-Wallace coalition was somehow unnatural or unstable with an analysis that sounds prescient of the Trump phenomenon forty years later:

The important thing about such [Reagan-Wallace] people is not that some of them reach their political position by reading Adam Smith while others do so by attending an anti-busing rally, but that all of them belong to a large and growing class of American citizens: Those who perceive themselves as victims of the liberal welfare state and its attendant costs. All that bubble-blowing about “populism” is a convenient way of concealing the interests such people have in common, thereby assuring that the welfare blocs and social engineers continue feeding on their hapless victims. It would be foolish to suggest that there are no differences between the Reagan and Wallace forces. Of course there are differences, as there are between any two political groups, or between any two human beings. But the point of political coalitions is precisely to bring together elements that have more in common than they do apart—and that is a description that applies with perfect relevance to the followers of Reagan and Wallace.

But the heart of the article was a spirited defense of Reagan’s devolution plan on the merits of long-familiar Evans themes about decentralized government and an extension of the political logic behind the new third-party idea.

Then the third major difficulty facing a third-party presidential campaign beyond ballot access came into play but in a way that worked out well for the Reagan cause while ending, as a practical matter, any momentum for a new third party: finance. The new campaign finance rules passed in 1974 as amendments to the 1971 Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) restricted both contributions and spending in ways highly adverse to any third-party campaign or independent expenditure effort such as ACU’s Conservative Victory Fund. Naturally Evans understood that such reforms would make political corruption worse as well as being “a blatant assault on our political liberties.” Evans and ACU had a plan for the new regulations, too: a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of FECA on First Amendment grounds. Senator James Buckley of New York became the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit that became Buckley v. Valeo, but Evans and the ACU signed on as coplaintiffs (along with the ACLU and Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy). Covington & Burling agreed to take on the case pro bono, with the lead brief preparation work done by a young lawyer with a bushy mustache named John Bolton. But even with pro bono representation, there were still considerable expenses for such a case (about $15,000 before oral argument), which ACU agreed to pick up.

…

The Buckley case was argued at the Supreme Court on November 10, 1975, with the Court issuing its ruling with unusual speed (likely owing to the need to settle the matter before the 1976 campaign cycle began in earnest) on January 30, 1976. In a complicated ruling with several splits among the justices over different questions at issue, the Court ruled that both campaign spending limits and independent expenditures for or against a candidate were unconstitutional violations of the First Amendment, but it upheld the strict contribution limits. ACU was now in business to agitate on behalf of Reagan’s campaign, and just in the nick of time. “When the decision came down,” ACU political director James Roberts recalls, “ACU’s offices were in the Human Events building, and [publisher] Tom Winters came down with a copy of the decision and told us, ‘The way I read this, ACU could do an independent expenditure effort for Reagan.’ And that’s where the whole idea came from.”

Some early polls showed Reagan surging ahead of Ford nationally and in the New Hampshire primary. Instead, Reagan lost New Hampshire narrowly (perhaps because of the attacks on his $90 billion budget cut plan), and his campaign went downhill from there, losing the next five primaries to Ford, including the crucial Florida primary. The Reagan campaign was on the brink of final collapse on the eve of the North Carolina primary, and behind the scenes his campaign was secretly negotiating his exit from the race with the Ford campaign over how much help Reagan could get from Ford to retire his campaign debts in return for dropping out. Reagan and his senior staff left the state the day of the primary assuming they were going to lose. It looked like the end of the line (though Reagan was telling everyone who would listen that he would not drop out).

Roberts said that “we didn’t think that the Reagan campaign was nearly as tough as they should have been on Ford and nearly as conservative as they should have been. And so we decided to fix that problem with our ads. The Reagan people were throwing in the towel [in North Carolina].” The ads centered around the theme “Reagan and Ford—there is a difference.” “And then we had listed all the other differences,” Roberts recalls. ACU cut two television ads, several radio spots that ran over eight hundred times, and a newspaper ad placed in twenty papers, spending $172,000 in all. Evans flew to North Carolina to announce the effort and made a tour of the state “in a little prop plane that seemed to be made out of canvas, and it was terrifying the whole time,” Roberts says. “In fact, after the primary we heard the plane crashed, so it was literally touch and go.”

Reagan’s upset victory in North Carolina breathed new life into his campaign and is often regarded as the key moment in Reagan’s drive to the presidency. Had he dropped out after a loss in North Carolina, it is unlikely he would have run successfully in 1980. Lou Cannon, the journalist who followed Reagan longer than any other, wrote that “North Carolina was the turning point of Reagan’s political career.” Jameson Campaigne Jr. is not alone in judging that “Without Stan Evans, it is quite likely there would have been no Ronald Reagan in 1980.”

Read more in M. Stanton Evans: Conservative Wit, Apostle of Freedom.