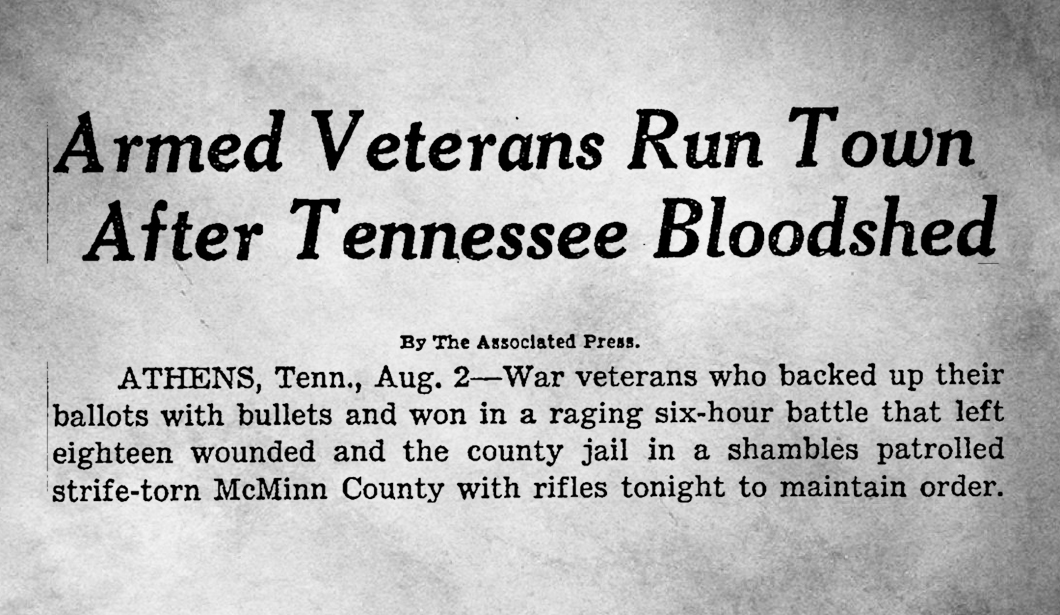

In 1946, a group of soldiers returning to their hometown of Athens, Tennessee after World War II became fed up with the corruption and brutality of the county’s Democratic political machine. Under the leadership of boss E.H. Crump, the machine dominated politics by intimidating, assaulting, and outlawing the opposition—in one instance, abolishing the independent judicial review of election results and giving the job of counting ballots to the Sheriff’s Department, which was run by Crump’s cronies.

The sheriff’s office operated on a fee system whereby deputies were paid for each citation they issued and suspect they booked. Deputies often cited or arrested citizens on falsified charges for a quick buck—sometimes more than $100 per week—and frequently stopped buses on their way through the county in order to charge every sleeping passenger with public drunkenness. Others demanded payoffs from local businesses to ignore gambling or prostitution on the premises.

.

Political protests against these practices did no good, because deputies bribed or intimidated voters, stole ballot boxes, or paid minors to vote and because many state officials were themselves members of the Crump gang. Federal attorneys brought corruption charges against local officials, but judges and juries were too fearful to stem the abuse.

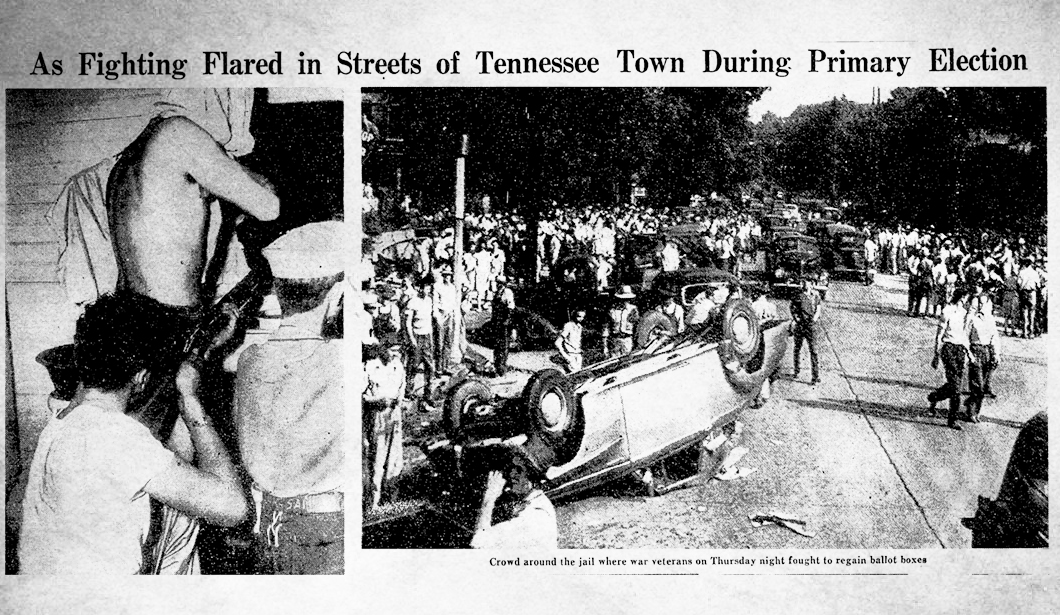

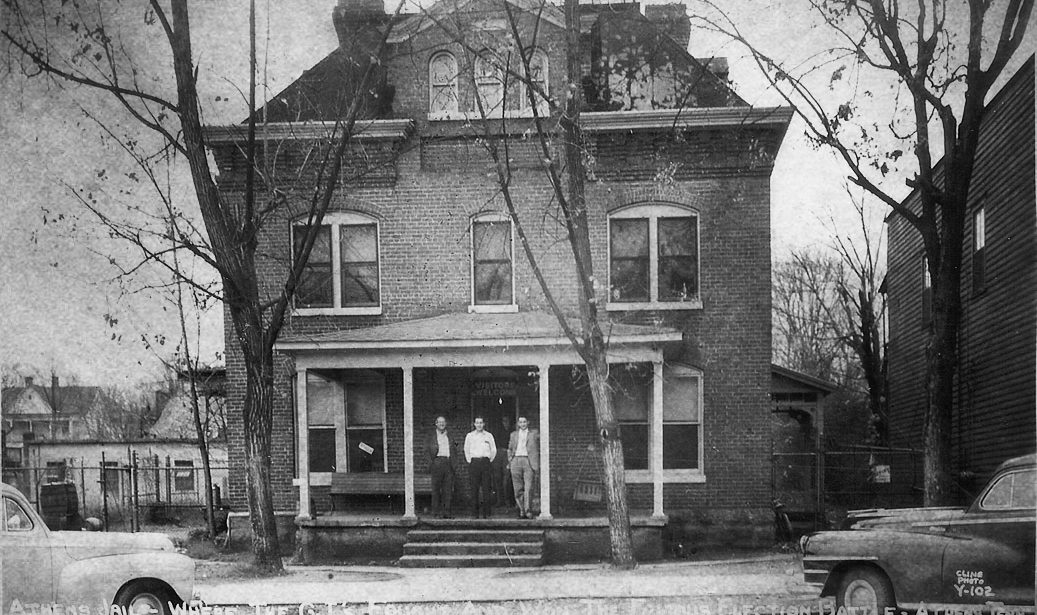

Finally, frustrated veterans decided to act. They met secretly to form their own political party, the “G.I. Ticket,” which included a veteran candidate for each countywide office, and issued a platform promising that under their leadership, “every ballot will be counted.” Knowing the danger they faced, the group asked the governor and the federal Department of Justice for protection. All refused. On August 1, election day, the sheriff brought in 200 armed “special deputies” to menace the voters. One G.I. Ticket poll watcher was arrested when he disputed whether a voter was qualified. Other veterans were kidnapped by deputies who took them to the county jail or dropped them off naked in the woods to keep them from reaching the polls. At one precinct, officers pulled guns on G.I. observers, who fled by leaping through a plate-glass window. Later, a group of officers led by a deputy named Windy Wise beat black veteran Tom Gillespie with brass knuckles when he came to vote. When Gillespie tried to run away, Wise shot him in the back.