If you’re old enough to remember the Soviet Union, you’ve probably wondered why so many young people today seem attracted to socialism. One influence is Howard Zinn, who published A People’s History of the United States in 1980, the year before the first millennials were born.

The book “continues to be assigned in countless college and high-school courses, but its commercial sales have remained strong as well,” The Chronicle of Higher Education reported in 2003, on the occasion of its millionth copy sold. It kept selling after Zinn died in 2010: The Zinn Education Program website now claims more than two million sales.

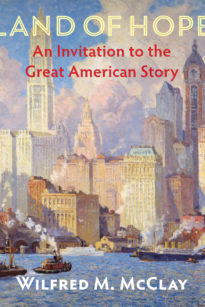

Historian Wilfred McClay aspires to be the antidote to Zinn, whom he accuses of “greatly oversimplifying the past and turning American history into a comic-book melodrama in which ‘the people’ are constantly being abused by ‘the rulers.’ ” Mr. McClay’s counterpoint, which comes out next week, is titled Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story.

Too many students are drawn to Zinn because the standard textbooks are visionless and tedious.

He says he doesn’t mean his new book as “some saccharine whitewash of American history.” But he’s seen too many students drawn to Zinn because the standard textbooks are visionless and tedious. “Just as nature abhors a vacuum,” Mr. McClay says, “so a culture will find some kind of grand narrative of itself to feed upon, even a poisonous one.”

A lousy story is better than no story at all: “We historians have for years been supplying an account of the American past that is so unedifying and lacking in larger perspective that Zinn’s sweeping melodrama looks good by comparison. Zinn’s success is indicative of our failure. We have to do better.”

With his round dark-framed glasses and bushy, graying mustache and eyebrows, Mr. McClay, 67, looks as if he could have walked out of a 1950s classroom. He’s taught history since 1986, including at Tulane, Johns Hopkins, the University of Tennessee and now the University of Oklahoma. He takes a decidedly traditional approach to studying and teaching history, and he bristles with criticism for fashionable nostrums.

Don’t ask him who’s on the right or wrong side of history. He thinks those concepts are bunk. “History is only very rarely the story of inevitabilities,” he says, “and it almost never appears in that form to its participants.”

Mr. McClay’s objective in “Land of Hope” is to help readers develop a sense of perspective and “a mastery of the detail” of American history.

Thus in the new book he observes that it’s “hard to read about” early-19th-century America “without thinking of the series of events culminating in the coming of the Civil War as if they were predictable stages in a preordained outcome. Like the audience for a Greek tragedy, we come to this great American drama already knowing the general plot,” and susceptible to the illusion that it was written in advance. He urges readers to resist “that habit of mind” and remember that people at the time had no foresight to match our hindsight.

What gets him most riled up is what he sees as an abdication. “When you teach an introductory course in American history,” he says, “you really have a responsibility . . . to reflect in some way the national story, in a way that is conducive to the development of the outlook and skills of a citizen—of an engaged, patriotic, serious citizen.” Most professional historians don’t “take that mandate very seriously at all,” and instead provide “a basically negative understanding of American history.”

He says proudly that they reciprocate his aversion. When he meets colleagues at conventions and tells them the name of his book, “they just kind of look at me and say, ‘Oh my God, what have you been smoking?’ . . . When I say it has the word ‘Great,’ in ‘the Great American Story,’ then they’re even more dubious.”

Mr. McClay’s objective in Land of Hope is to help readers develop a sense of perspective and “a mastery of the detail” of American history. The Zinn approach allows them to be lazy: “Why learn what the Wilmot Proviso was, or what exactly went into the Compromise of 1850, when you could just say we had this original sin of slavery?”

Read the full article at The Wall Street Journal.