Ben Weingarten: Yes, and it’s an aesthetically pleasing product as well as an intellectually stimulating one. And let’s start right from the title of the book: David’s Sling. It has a double meaning. Explain that to our listeners.

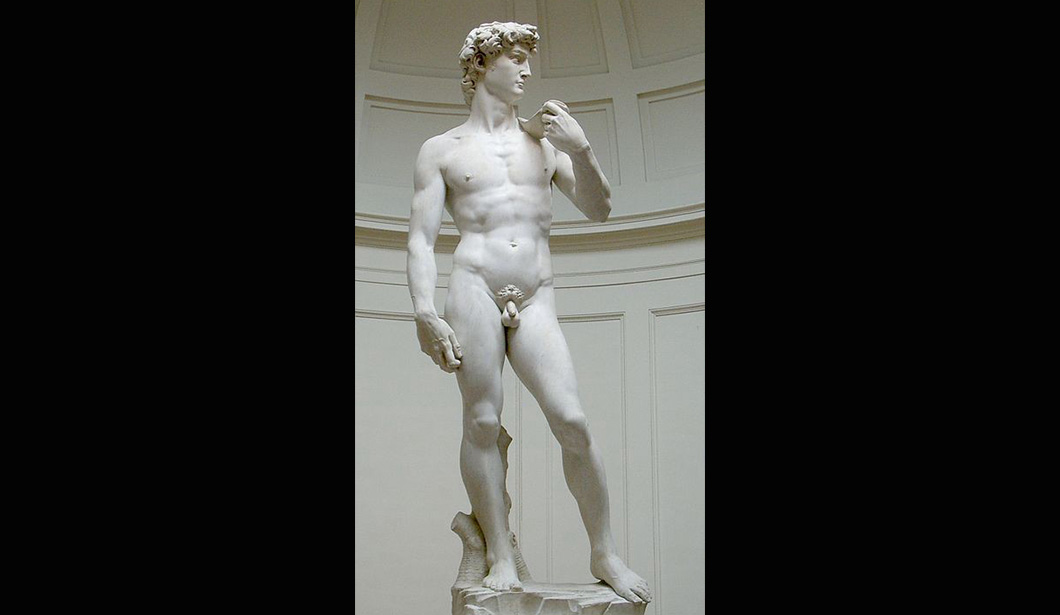

Dr. Victoria Coates: Well, I think most people are familiar with the story from the Book of Samuel of David the shepherd who would go on to be the great king of Israel, and the founder of the house that produced Jesus Christ. But at the beginning he was just a simple shepherd, and the Israelites were battling the Philistines. And the Philistines had a great giant named Goliath who came out and taunted the Israelites, and asked them to join in single combat. And they didn’t have anyone brave enough to do it. So David came along and said he would. And because he was so pure in his faith in G-d, and also so ingenious and skillful with his slingshot, he was able to defeat the giant. And so, as I was looking at this project which originally started just focusing on Michelangelo’s David, it seemed to me the slingshot by which David was able to kill Goliath was really the metaphor for democracy.

Ben Weingarten: And America of course as sort of an underdog nation, and when you think about technology and art and advancement as well, the entrepreneur is the seminal underdog figure. So there really are a number of primary and secondary and tertiary meanings that one can interpret from the title of your book as personified in David and his sling. Now looking at sort of the opposite side of the coin, one piece of architecture that you reference and you have a chapter about is the Parthenon. I visited the Parthenon a couple of years ago and was struck by the fact that here was a symbol of democracy by the classical definition of democracy, as the height of civilization, and yet today it’s surrounded by what is basically a decaying country. And that sort of shows the rise and fall, and that democracy isn’t something that’s guaranteed, it needs to be protected. Speak a little bit to the significance of the Parthenon.

Dr. Victoria Coates: Oh absolutely, and the only problem Ben is you’re about 2,300 years late because the Athenian experiment in democracy was dramatic, it was original, it was the first one, and it failed in about 150 years. So one of the great lessons of David’s Sling is that freedom is not inevitable. And certainly going back to what you were just saying about the United States being an unlikely hero, all of these states are. I mean…Rome is a swamp. Venice shouldn’t exist at all. Holland is underwater. Florence is flat. It’s a market town. These are not places that you would assume are going to flourish. But because of the remarkable effects of democracy, and particularly democracy when married to free market principles — which is really central to the Florence, Venice and Holland chapters — you have this remarkable both economic and creative flowering that allows for the creation of the works of art that each of these chapters study. So I think it’s certainly not an exclusive arrangement between freedom and creative genius, but we have a wonderful pattern of these over time, which when we trace them I think gives us a new appreciation for what Western Civilization has accomplished.

Ben Weingarten: There’s also an element of creative destruction in terms of political systems when you think about the fact that our Founders saw the failures of all of these systems including the dangers of democracy qua democracy — pure democracy — and chose a republican form, and so you see that we build on the vestiges of these past civilizations. Now you highlight nine other pieces of architecture or art as well in your book. What are one or two of the other pieces or locations that you’d like to highlight for our listeners?

Dr. Victoria Coates: Well it’s a little hard because each one of them was a wonderful learning experience for me, even ones that I had taught and studied for many years because this line of inquiry — the notion that democracy would inspire great art — is not very fashionable in the academy right now. So none of these works have really been looked at in this context. And, one of the ones that might be very surprising to your listeners is St. Mark’s [Basilica] in Venice, which most people think of as the “cathedral of Venice.” It’s nothing of the sort. It’s the palace chapel of the duly elected leader of Venice, the Doge, and it was built as kind of a treasure box to be the manifestation of the wealth that was generated by the remarkable advances in shipping and bookkeeping that were achieved by the Venetian Republic. And then on top of that, they added in wonderful antiquities like the beautiful bronze horses that are over the door to the church, which were brought back on the Fourth Crusade from Constantinople, and became the symbol of Venice as the inheritor of the mantle of Antiquity in the Middle Ages. And to have this very physical reminder in Venice was now the new Athens, and was going to take that role going forward.

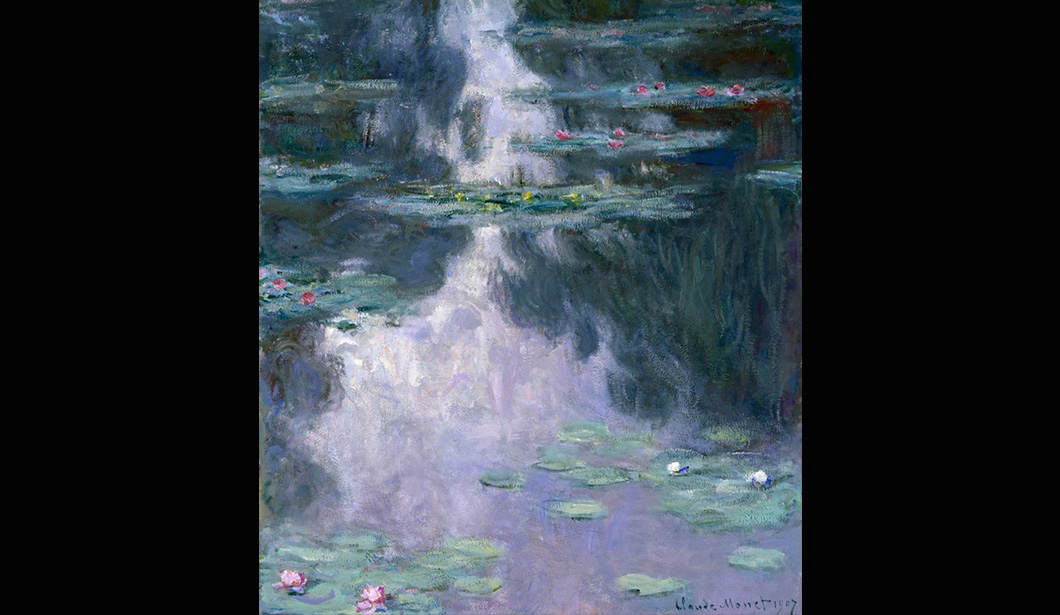

An equally unexpected one is Monet’s Water Lilies from the 1920s. Most people don’t think of Monet as a 20th century artist, and certainly not a particularly political one. But the fact of the matter is the…cycle that’s installed in the Orangerie [Museum] is done very deliberately to celebrate the victory in World War I. And it was a very personal communication between Monet and Georges Clemenceau to…celebrate the preservation of the Third Republic. And Monet was a very passionate French patriot. So I think there’ll be some unexpected stories in there.

Ben Weingarten: One of the tensions that I noticed — and when you think about culture more broadly, it’s always looming in the background — is that these works of art throughout history have been financed because wealth was created and there was an ability for people to indulge in the arts and spend on the splendor of these various civilizations. Yet so frequently when you look at the intelligentsia in general and artists in particular, they have such a Leftist worldview. So how do you tie that to the idea that freedom and prosperity and art go hand in hand, yet the artists who themselves are pure entrepreneurs in reality, typically have a worldview so anathema to the system in which they live and create.

Dr. Victoria Coates: Well I actually blame Michelangelo for all of this. It’s really his fault. And I don’t think he did it on purpose, but he really pioneered the notion of the artist as the independent creator. And it’s in many ways ironic because Michelangelo at the same time was a committed patriot, he was a devout proponent of the Florentine Republic and I don’t think he would have done what he did with the intent of divorcing artists from participation in free systems in a way that we would consider to be salutory. But that’s sort of been the effect.

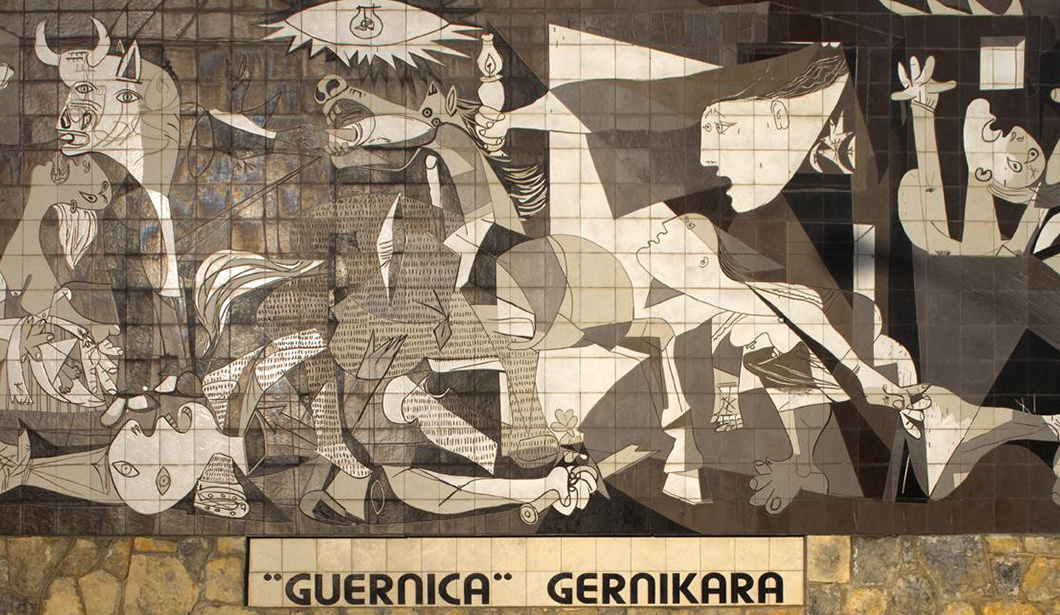

And what’s maybe the most interesting case study is Picasso because Picasso — he’s the last chapter, he’s the 10th chapter, and he painted the great Guernica in the late 1930s to protest against the dramatic Nazi and Franco combined bombing of the Basque town, terrible slaughter of civilians which was sort of a test-run for the Luftwaffe. But because of the advances in communications, rather than just sort of being buried, the event was telegraphed around the world within hours with pictures. So everybody saw the slaughter and the destruction. And Picasso who was in Paris at the time and had been commissioned by the exiled Republic of Spain to do a major mural for their World’s Fair pavilion, and had been struggling with it, said “I have my subject.” He said, “I’m not generally a political artist, but I want to do this.” And he paints the great protest picture, this massive black-and-white fractured image of destruction. And what’s so ironic in Picasso’s case is he could see the existential threat of the Nazis. He understood they weren’t just trying to take over one state, they were trying to extinguish liberty. But he couldn’t see it with the Soviets. He couldn’t see it with Communism. Or he wouldn’t see it. And so while on the one hand he was able to embody the resistance to one existential threat of the 20th century, he couldn’t see the other.

Ben Weingarten: Applying your thesis about democracy and liberty more broadly going hand in hand with artistic creation and flourishing, if you were to look at that thesis in today’s society which in the West is increasingly — and hopefully swings the other way — an illiberal liberal bastion, do you suspect that artistic creation will decline proportionate with the growth of this sort of progressive, squelching creative and artistic freedom kind of mindset?

Dr. Victoria Coates: I think it’ll probably move to an unexpected place. And one of the most interesting examples from the last maybe 15 years is [Chinese artist] Ai Weiwei’s Bird’s Nest from the 2006 Olympiad in Beijing because this was supposed to be an expression of China’s embrace of the Greek tradition — I mean the Olympics originating in ancient Greece, so a symbol of democracy, and Ai Weiwei — a great artist and designer — is going to put up this stadium that will imitate the monuments of ancient Greece. But after the Olympiad he came out and said “Look. This thing [the Olympics] is a false smile. It’s not real. These people [the Communist Chinese leaders] are not liberalizing in any way.” And he’s a very controversial figure, but I think he understood how basically he had been exploited, and what the PRC [People’s Republic of China] was all about shows you that these forces are still at work. So it would be hard for me to predict precisely when it would appear again, but it does seem to me that given the spread of democracy, and the fact that we now — when 70 years ago Israel didn’t exist, and Japan was a deadly enemy — we now have two terrific, vibrant democratic allies there for the United States, that we might look to either or both of them for places where the values that have produced these previous masterworks might resurface.