On October 3, 1789, George Washington, responding to a request from the First Congress of the new United States, issued the first-ever presidential proclamation. He named the last Thursday of November of that year as a “day of public thanks-giving,” a time for Americans to express gratitude to God for “the civil and religious liberty with which we are blessed” and for the recent establishment of a “form of government for their safety and happiness.” Eight weeks later, on Thursday, November 29, Americans throughout the thirteen states came together for the first time to give thanks as a nation.

Sarah Buell was one year old on that first national Thanksgiving Day, too young to remember the celebrations that took place throughout the land. Newspapers published Washington’s proclamation, states held public functions in honor of the day, houses of worship opened their doors for religious services, citizens—including Washington himself—made donations to help the poor, and families gathered for festive meals. Hale gave a tip of the hat to Washington and the first national Thanksgiving in her 1827 novel Northwood by placing a portrait of the first president in the room where her fictional Yankee family was celebrating the holiday.

Seventy-four years and fifteen presidents later, Abraham Lincoln became the second president to ask all Americans to come together to celebrate a day of national Thanksgiving. The thread between Washington’s Thanksgiving Day and Lincoln’s was Sarah Josepha Hale.

.

.

Hale didn’t invent the American festival of Thanksgiving. But it was thanks to her that the holiday became a permanent fixture on the American calendar. Without Hale, we might still be stuck at the point at which she began her campaign for a common Thanksgiving Day in 1847—with individual states celebrating the holiday on separate dates that had been designated by their governors and some states not bothering to celebrate at all. Hale used her influence to encourage the celebration of Thanksgiving in every state and territory and to advocate for a common Thanksgiving Day.

Hale didn’t invent the American festival of Thanksgiving. But it was thanks to her that the holiday became a permanent fixture on the American calendar.

By the time Hale became editor of the Lady’s Book in 1837, the Thanksgiving tradition had spread beyond New England to other states and territories, often carried there by migrating New Englanders. If a state celebrated Thanksgiving—some did not—selection of the date was left to the governor. The president sometimes named a Thanksgiving Day in federal territories. But there was no uniform date for the holiday.

By tradition, Thanksgiving Day fell in the fall. Depending on the date decreed by their governor, Americans celebrated the holiday anytime between late September and early December. In 1837, Hale was a resident of Massachusetts, which marked the holiday on November 30. In her home state of New Hampshire, Thanksgiving fell a week later, on December 7. Pennsylvania, where the Lady’s Book was published, did not celebrate Thanksgiving that year.

Hale loved Thanksgiving with a passion that other mothers feel for their favorite child. She wanted every American, in her day and forever more, to share her ardor. She accurately forecast that the time would come when all American citizens across the country, and no matter where in the world they might find themselves at the end of November, would pause to give thanks on a common Thanksgiving Day.

As a homegrown holiday, Thanksgiving was dear to Hale on several counts. It fit into her journalistic mission of helping the new country develop a common culture, something that would differentiate Americans from their former colonial masters. Today Thanksgiving is linked inextricably with the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Indians and their now-famous feast of 1621. But if you had mentioned them to Hale, she would have looked at you blankly. The story of the harvest feast of 1621 was lost to history until the middle of the nineteenth century, when Pilgrim documents

that had gone missing for two centuries came to light.

As a religious matter, Hale saw Thanksgiving as embodying a founding principle of the United States—freedom of worship.

As a religious matter, Hale saw Thanksgiving as embodying a founding principle of the United States—freedom of worship. Protestantism was the dominant religion of the period and Hale sometimes referred to Thanksgiving as a Christian tradition. But she recognized that, like America itself, the holiday was open to people of all faiths, a point Washington stressed in his Thanksgiving proclamations. In 1795, he called on “all Religious societies and Denominations . . . to set apart and observe . . . a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Praise.”

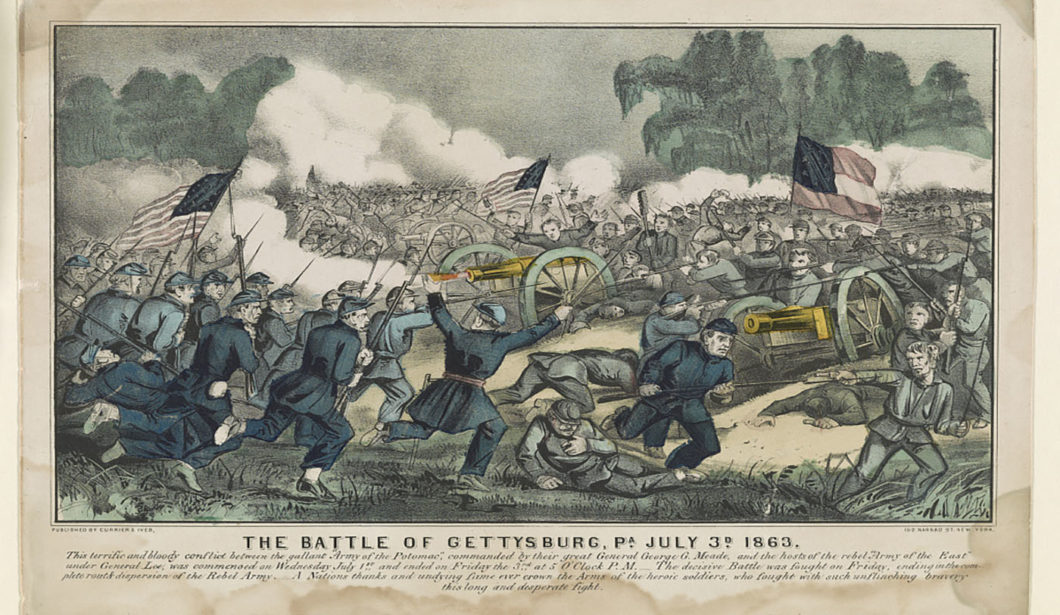

Hale was intrigued by the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, or the Feast of Weeks, and often cited it as one of the roots of the American holiday. She pointed to God’s command to the Jews in the Old Testament book of Nehemiah to celebrate a harvest festival—and she believed that His command applied just as much in times of war as in times of peace. “In a time of national darkness and sore troubles,” she wrote in 1863, “shall we not recognize that the goodness of God never faileth, and to our Father in heaven we should always bring the Thanksgiving offering at the ingathering of the harvest?” Her words have added meaning when it is realized that she wrote them shortly after the bloody battle of Gettysburg.

She also saw Thanksgiving as a time for expressions of patriotism, on a plane with the Fourth of July and Washington’s birthday, the only other national holidays born of the American experience. The fact that Washington, whom she admired above all other men, saw the value of a national Thanksgiving Day, elevated its status in her mind. An additional selling point was that while Thanksgiving took place in the autumn, Independence Day fell in the summer and Washington’s Birthday—February 22—was a winter holiday. This was a trivial consideration, to be sure, but Hale cited it to build support for her proposal. She also applauded the fact that a late-November Thanksgiving meant that the “war of politics”—that is, elections—“will be over for the year.”

***

The public part of her Thanksgiving campaign unfolded in the pages of the Lady’s Book in a series of articles published over the course of seventeen years. The Lady’s Book, with its tens of thousands of readers, was a powerful platform, and she used its pages to carefully build a consensus for a common nationwide Thanksgiving Day. Hale saw Thanksgiving, with its emphasis on gratitude to God, family reunions, and a special meal, as falling into the feminine sphere. Her readers were located in every state and territory. Hale understood that if they got behind her call for a national Thanksgiving, politicians would likely pay heed.

***

Separate from her Lady’s Book campaign, Hale privately sought the support of elected officials and other public figures. Tapping into what would today be called her personal network, she wrote hundreds of individual letters to statesmen and other opinion makers urging them to lend their prestige and clout to her idea for a common Thanksgiving Day. Considering that each letter was written by hand and personalized for the recipient, it was an enormous task.

“If every State should join in union thanksgiving on the 24th of this month...would it not be a renewed pledge of love and loyalty to the Constitution of the United States, which guarantees peace, prosperity, progress and perpetuity to our great Republic?”

Her initial goal was to persuade every governor to agree on a date for Thanksgiving. As the years went by, she came to believe this that wasn’t a practical solution. It would require a permanent campaign to make sure that every governor cooperated every year on the date for that year’s Thanksgiving Day. Politics or personal preference inevitably would interfere, leading one or more governors to go his own way, choosing a separate date for his state’s celebration. As Hale diplomatically put it in her letter to Secretary of State Seward making the case for a presidential proclamation naming a national Thanksgiving, a governor might “have special purposes to answer or will forget the importance of cooperation.” Her preferred path to a national Thanksgiving was to find a president willing to do what Washington did: issue a proclamation designating a date for the holiday to be marked nationwide.

***

The moral influence of a communal holiday was a theme to which she often returned, especially as the country moved toward civil war. Hale hoped that a national celebration of Thanksgiving would help preserve the Union. “Such social rejoicings,” she editorialized in 1857, “tend greatly to expand the generous feelings of our nature, and strengthen the bond of union that finds us brothers and sisters in that true sympathy of American patriotism.”

.

.

In 1859, she again stressed her belief in the unifying impact of a national Thanksgiving: “If every State should join in union thanksgiving on the 24th of this month,” she wrote, “would it not be a renewed pledge of love and loyalty to the Constitution of the United States, which guarantees peace, prosperity, progress and perpetuity to our great Republic?”

Even as war loomed, Hale renewed her argument, writing that a national Thanksgiving could help keep together the divided country. “This year the last Thursday in November falls on the 29th,” she wrote in 1860. “If all the States and Territories hold their Thanksgiving on that day, there will be a complete moral and social reunion of the people of America. Would not this be a good omen for the perpetual political union of the States?” There was a note of desperation in her plea. By the time the next autumn rolled around, the United States was engulfed in civil war. In 1861, Hale sought a Thanksgiving Day of Peace, pleading that “we lay aside our enmities and strifes . . . on this one day.” Her entreaty went unheeded.

By 1860, Hale was close to achieving her goal of seeing Thanksgiving celebrated in every state on the same day. In 1859, thirty of the thirty-three states had celebrated on November 24, the last Thursday of the month. Two of the ten territories—Nebraska and Kansas—also celebrated on that date. Success was near at hand. Thanksgiving was celebrated, too, by an increasing number of Americans living abroad, and Hale published accounts about Thanksgiving celebrations in India, China, Switzerland, and elsewhere.

At the same time Hale was working with governors to orchestrate a de facto national Thanksgiving Day, she was quietly pursuing another path—one that, if successful, would relieve her of the task of seeking the annual approval of every governor. She hoped to persuade the president of the United States to follow Washington’s example and issue a proclamation declaring a national Thanksgiving Day.

***

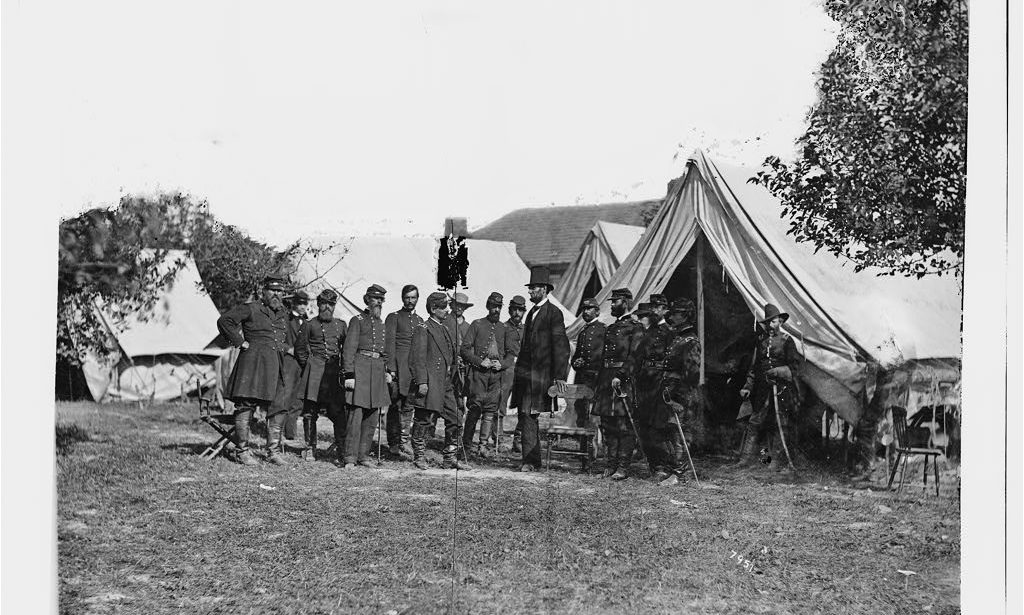

Hale family lore has it that their famous ancestor traveled to Washington in 1863 for a personal interview with Lincoln on Thanksgiving. Years after her death, a grandson, Charles Hale, son of Horatio Hale, told an interviewer, “I remember my father saying that his mother had visited President Lincoln and had found him a very kindly and interested gentleman.” He added no details about the meeting.

Lincoln was famously approachable, and the well-known editor of the Lady’s Book surely could have secured an interview with the president on the basis of her professional standing alone. She also had a family connection that she could have used to facilitate a request. Major General David Hunter, a longtime friend of Lincoln and an honorary pallbearer at his funeral, was the older brother of Hale’s son-in-law. Dr. John Hunter married Hale’s daughter Frances in 1844. An introduction from Major General Hunter would have opened doors at the White House.

While a meeting between Hale and Lincoln is entirely plausible, there is no evidence to support it other than the secondhand recollection of her grandson years after the presumed meeting took place. Hale never wrote about it, and there is no mention of it in the papers of Lincoln’s presidency.

Rather, the evidence shows that, as she had done with other presidents, Hale made her case to Lincoln for a national Thanksgiving in a letter. Her first step was to write Secretary of State William Seward. They had met in Philadelphia some years previously and she regarded him as a friend.

.

.

Writing Seward was a strategic move. Hale correctly surmised that he would be receptive to her proposal for a national Thanksgiving. As governor of New York from 1839 to 1842, Seward had issued four Thanksgiving proclamations. Each was a beautiful piece of prose, lyrical in its descriptions of American abundance and American liberty. According to his son Frederick, Seward always found this aspect of his gubernatorial duties a particular pleasure. His Thanksgiving proclamations were “no mere form,” Frederick recalled, but heartfelt expressions of Seward’s belief that the American people have, in all the world, the greatest grounds for giving thanks. Seward was second to none, too, in his enjoyment of the day itself. He recorded in his memoirs the “fine roasted turkey and . . . venison-steak” that his wife Harriet served him and his law clerks on Thanksgiving Day 1836.

His memoirs show that as governor, Seward was well aware of the disparity in the dates on which states celebrated Thanksgiving. In 1841, he designated Thursday, December 9, as the date for the holiday in New York. That same year the governor of Ohio designated December 21 and the governor of Rhode Island named November 25—giving truth to the witticism that a traveler with a well-planned itinerary could enjoy a Thanksgiving dinner on each Thursday between Election Day and Christmas Day.

In Hale’s lengthy letter to Seward, dated September 26, 1863, Hale reviewed the history of her campaign for a national Thanksgiving and made a case for why a presidential proclamation would be the best way to achieve that goal. Waiting for every state to legislate a fixed date would take too long, she explained, and it was unrealistic to expect that every governor would agree on a common date every year.

Taking a cue from Washington, she recommended that Lincoln “invite and recommend” the governors to unite in approving a date chosen by the president, thereby skirting constitutional objections. She concluded by urging the president to move quickly. The presidential proclamation should be issued by the following week. The brashness—effrontery even—of Hale’s request to a wartime president was typical of her self-confidence and her devotion to her cause.

Hale was in such a hurry that she didn’t wait for Seward’s reply. Two days after she posted her first letter to Seward, she wrote directly to the president, imploring him to declare a day of national thanksgiving. “Thus, by the noble example and action of the President of the United States,” she wrote, “the permanency and union of our Great American Festival would be forever secured.”

Events moved swiftly after that. Seward’s reply to Hale, dated September 29, 1863, informed her that he had received her “interesting” letter and had “commended [it] to the consideration of the President.” On October 3—only seven days after Hale’s initial letter to Seward—Lincoln issued his Thanksgiving Proclamation naming Thursday, November 26, as Thanksgiving Day.

Not since Washington had a president called on Americans to come together to give thanks for their joint blessings as a nation. Lincoln’s proclamation was the first in what has become an unbroken string of Thanksgivings up to the present day.

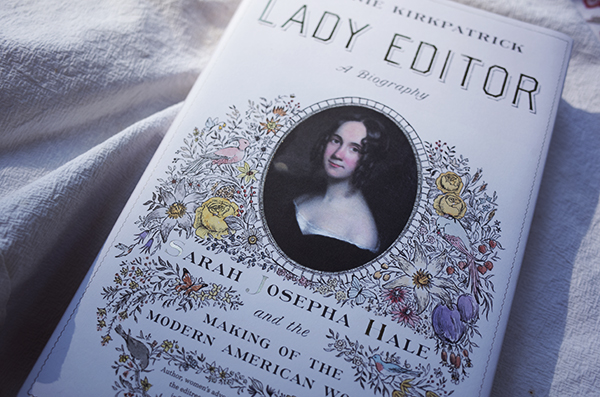

Read more in Lady Editor: Sarah Josepha Hale and the Making of the Modern American Woman.