Excerpted from a review in the Wall Street Journal by Michael F. Bishop

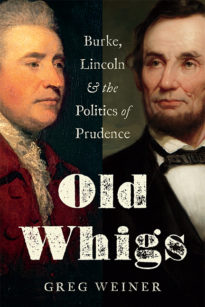

In a time like our own, with its routine storms of controversy and spasms of outrage, a classical virtue like prudence may feel either quaint or hopelessly irrelevant. Among much else, Greg Weiner’s concise and elegant “Old Whigs” is a study and celebration of prudence, “for whose recovery,” the author believes, “contemporary politics aches.” He finds this now-uncommon virtue everywhere on display in the thought and statesmanship of Edmund Burke and Abraham Lincoln, the Whigs of his title.

But what is prudence? To Mr. Weiner, it “involves a carefully choreographed dance between principle and circumstance.” Far from seeking an earthly paradise, the prudent leader pursues gradual reform. Wise statesmanship rejects the extremes. But while the prudent leader is often cautious, he is not timid. “The key to prudence,” Mr. Weiner writes, is “having the capacity of judgment that can distinguish between ordinary moments and genuine crises and, in either case, calibrating action to proper goals.”

“Old Whigs” is a study and celebration of prudence, “for whose recovery,” the author believes, “contemporary politics aches.”

Both Burke and Lincoln indeed personify prudence, but at first they seem an unlikely pair. They made their name in different eras; Burke died a dozen years before Lincoln was born. Burke was born in Dublin, the son of a lawyer, Lincoln in a Kentucky cabin built by his illiterate father. The Irishman became a tribune of the aristocracy, the American a champion of the common man. Lincoln didn’t read Burke; rather he admired Thomas Paine, Burke’s great rival.

Yet they had much in common. Both yearned for distinction and achieved it by their own merits: Burke proudly declared himself a “novus homo”; Lincoln gloried in being a self-made man. Both were Whigs in their respective contexts, suspicious of executive power and respectful of legislative prerogatives. Their essential Whiggism persisted in the face of political crises, whether Burke’s estrangement from his party colleagues over their support of the French Revolution or the dissolution of Lincoln’s Whigs and their absorption by the new Republican Party.

Both Burke and Lincoln indeed personify prudence, but at first they seem an unlikely pair.

Both were literary craftsmen of the highest order. Mr. Weiner, the provost and vice president for academic affairs at Assumption College, quotes these supremely quotable men at length. So wise and enduring are their words that the reader can almost hear the sound of a chisel on marble. Burke’s writings and orations were fired with passion and exuberance, glorying in European traditions, while Lincoln’s greatest utterances were austere and exquisitely balanced—and unmistakably American.

Read the full review at The Wall Street Journal.